A rifle and a shovel — As a wagoner in World War I, early Pablo Beach resident made his mark in history.

By Johnny Woodhouse

The oldest headstone in Lee Kirkland Cemetery, the historic African-American graveyard in Jacksonville Beach, belongs to Jessie Butler, a native Floridian who performed back-breaking work in a seaside mining camp known as Mineral City before serving his country overseas in World War I.

The upright marble headstone, issued by the U.S. Government, denotes the little-known unit he served in during the war, and, most importantly, his rank – that of wagoner.

Born in Fort White, Fla., in 1892, Butler moved to Jacksonville with his mother and younger siblings on or before 1910, according to U.S. Census records. Fatherless at the time, Butler, then 17, and his family members lived in a boarding house where both his mother and younger sister earned money washing clothes.

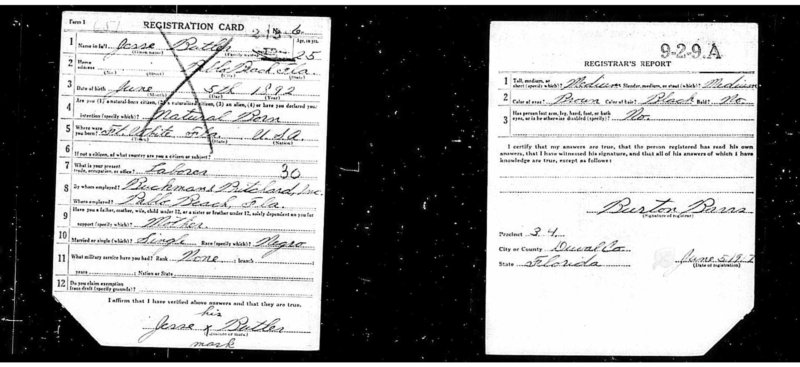

According to census records, Butler worked two jobs in 1910, including as a carpenter for Jacksonville resident Pleasant Niblack. A skilled laborer for most of his short life, Butler listed his employer as Buckman and Pritchard, Inc. on his 1917 WWI draft registration card.

Henry Buckman and George Pritchard began mining the beach for rare minerals in 1916 after discovering a huge vein south of the St. Johns County line, according to “Turning sand into gold” by late historian Don Mabry. “World War I was raging in Europe and these elements were extremely valuable in weapons of war,” Mabry wrote. “Extracting it from the sand required machinery and men.”

And mules.

According to a 1918 Duval County draft board record, Butler, then 25, listed his occupation as teamster. In those days, a teamster was not a truck driver but a driver of a team of animals.

At the Buckman and Pritchard mining operation, mule teams were used to pull slip pans across the sand in order to unearth raw minerals like ilmenite, the most important ore in titanium. In all likelihood, Butler honed his teamster skills at the Buckman and Pritchard sand plant in Mineral City, which later became Ponte Vedra Beach.

Driving mule teams was a skill that was sought after by Army supply units during WWI.

A rifle and a shovel —

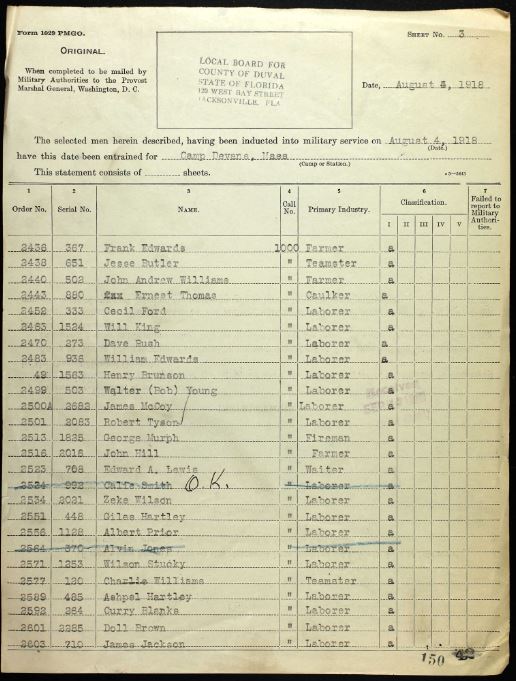

Butler was inducted into WWI service on August 4, 1918, with orders to board a train for Camp Devans, Mass. After about a month of stateside training, he was assigned to the 807th Pioneer Infantry Regiment, a replacement unit formed late in the war to construct roads, bridges, and railroads, often behind enemy lines.

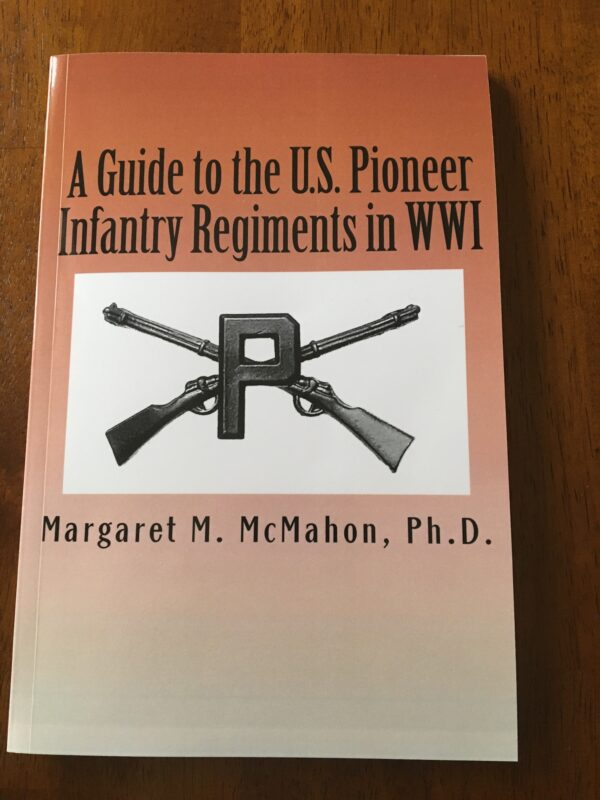

Of the 37 Pioneer Infantry Regiments formed in WWI, 26 served overseas and 15 saw combat, according to “A Guide to U.S. Pioneer Infantry Regiments in WWI” by Margaret M. McMahon, Ph.D.

The 807th was one of 14 African-American units that served overseas and one of seven that saw combat, taking part in the infamous Meuse Argonne Offensive in October 1918, the last major battle before the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.

Pioneer Infantry Regiments were typically comprised of more than 3,500 enlisted men trained in basic infantry tactics and combat engineering. They strung and removed barbed wire, filled holes left by enemy shells, and found and buried the dead from both sides, according to McMahon’s self-published book.

“They paved the way so troops and supplies could reach the front-line trenches, and they opened the way for advance troops moving forward to the attack,” the book said. “It takes a certain kind of soldier to go to war with a rifle and a shovel.”

Served under the French flag —

Of the 37 segregated Pioneer units formed in WWI, 17 were all-black with white commanding officers. The units were broken down into several companies. Due to his stateside skills as a teamster, Butler was designated a wagoner, a rank just below supply sergeant.

A supply company in a Pioneer unit included three sergeants (ordinance, supply and stable), and ranks for wagoner, horseshoer, and saddler. Mules were used to pull carts, wagons and mobile kitchens.

“The mules were used for draft. In some cases, the troops doing road repairs requested that trucks be replaced by wagons with mules because they were less dependent on road quality and could be pulled off the road more easily,” McMahon’s 2018 book said.

African-American units like Butler’s 807th served under the French flag, with some of its men earning the Croix de Guerre medal, awarded to foreign troops allied to France. As a unit, the 807th was awarded a Sliver Band by the French to wear on its regimental flag.

The unit was famous for its 52-piece regimental band led by Lt. Will Vodery II, a classically trained pianist who composed songs for the Ziegfeld Follies before the war.

After the armistice was signed, a number of Pioneer units, including Butler’s, remained overseas building new roads and other infrastructure.

An early demise —

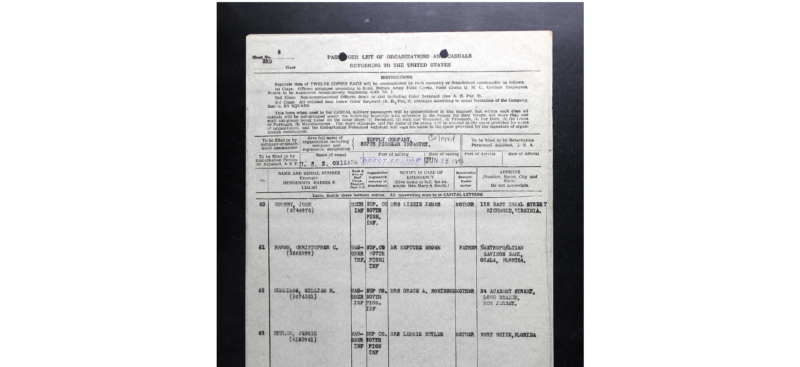

According to a passenger list for the USS Orizaba, a Navy transport ship, Butler and the rest of his regiment departed France on June 25, 1919, at the port city of Brest, a staging area for U.S. troops returning home. The 807th was officially discharged from service in July, 1919, at Camp Jackson, S.C.

After his WWI service, Butler listed his occupation as a laborer on 1920 census records. He resided on South 8th Street, Pablo Beach, listing his mother as a dependent.

His paper trail picks up six years later with distressing results. According to 1926 death records, Butler was the victim of homicide on Oct. 17, 1926. An autopsy report listed the cause of death as hemorrhaging from a shotgun blast to the abdomen.

Butler succumbed to his injuries at the county hospital in Jacksonville. He was only 32.

Four years later in February 1932, Butler’s younger brother, Joseph, applied for a government marker from the War Department. The marble stone was shipped to Butler’s mother on April 2, 1932, for placement in what was then known as the “colored cemetery” in Jacksonville Beach.

During WWI, more than 200,000 African Americans served with the American Expeditionary Force on the Western Front.

Jessie Butler, wagoner, was one of them.