This article was written by Spring 2019 Beaches Museum intern, Savannah Brychta

Without Jean H. McCormick’s decades of hard work and determination, much of the history of the Beaches’ area was in danger of being lost forever. Destined to fill a void many did not yet realize, Jean began her life as a proud and deeply involved member of the Beaches community.

The Hadens in front of the Oceanic Hotel (ca. 1929)

Jean Haden was born on May 1, 1921, in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father, a credit manager by trade, was advised by his doctor to seek out the coastal Florida air as treatment for his perennial health issues. At only six-years-old, Jean moved with her family to Jacksonville Beach, Florida. After settling in, her father purchased an old Catholic orphanage on the beachfront and converted it into the Oceanic Hotel.

Growing up within the walls of the Oceanic, Jean had the formative experience of watching her parents work hard to build and maintain a community institution. Her father managed hotel operations until his death, when Jean was sixteen. After that, her mother took over, eventually passing the hotel over to Jean herself. It was there that she interacted with the many characters that passed through the Oceanic’s doors, and it was there that she met J.T. McCormick.

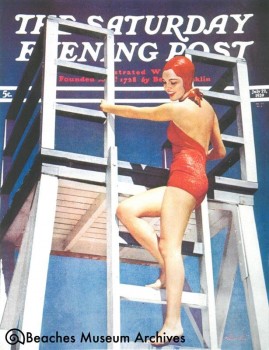

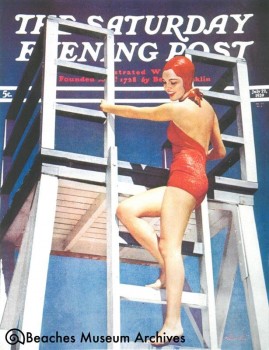

Jean McCormick on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post

In her early teens, the hotel was threatened by a violent tropical storm. Jean’s father called upon B.B. McCormick & Sons to construct an emergency bulkhead to shield his establishment from the expected storm surge. J.T. was one of those sons. The hotel survived and a romance was born. A few years later, J.T. and Jean began dating. Just before his death, Jean’s father told her that as long as she finished high school first, he would happily give his blessing for the two to marry. In 1939, Jean graduated from Duncan U. Fletcher high school and became Mrs. J.T. McCormick. The couple moved to the undeveloped Penman Road and started their family.

While J.T. followed in his father’s footsteps, expanding the community’s infrastructure, Jean became a significant member of the Beaches’ social structure. Her involvement in the community’s affairs grew to the point that she was able to identify societal needs and worked to fill them. Her passion and tenacity resulted in the establishment of a Dental Clinic for underprivileged children, the foundation of the Azalea Garden Circle, and the creation of a study group for local women to meet and discuss current events and other intellectual topics.

Phyllis Webb (left) and Jean McCormick (right) on the beach, photo by Virgil Deane (1948)

Jean also served as a president of the Junior Women’s Club of Jacksonville Beach. She served six years on the Jacksonville Episcopal High School Council and was vice president for two. She was president of the Women of Christ Church in Ponte Vedra Beach and president of the Friends of the Library at Jacksonville University. She served two three-year terms on the Jacksonville Historic Landmarks commission. She may not have realized it at the time, but working as a community leader in these organizations, Jean was building the skills and connections she later used to found a historical society. But it was that study group that planted the seed.

In 1976, in light of the nation’s bicentennial, Jean and the rest of the country began reflecting more on their collective pasts. Jean used it as an opportunity to research and talk about the history of the Beaches area with her study group. The local library offered only a single book on Beaches history. She was instructed to go downtown to find more.

Frustrated and motivated, Jean began to wonder why the Beaches were not the keepers of their own history. The Intracoastal Waterway (affectionately known as “the Ditch”) has long been a border between the Beaches area and Greater Jacksonville. As a result of this geographical divide, the communities on either side have evolved with some degree of separation, one that has birthed a distinct local identity at the Beaches. Jean began to wonder how one might go about preserving the story of that identity’s evolution.

By 1978, she was in contact with her old friend J.B. Dobkins who worked for the Florida Historical Society in Tampa. Under his advice, and with the support of her close friend Virgil Deane, Jean began taking the temperature of local interest in the idea of forming a Beaches Historical Society. The response was overwhelming. McCormick later recalled that the project’s momentum took on almost divine proportions. “The Lord meant this to be,” Jean told the Sun-Times in 1981 when talking about how “doors had been opened” to her in the early stages of her efforts. By 1979, the Beaches Area Historical Society had embarked on their mission to “Plan a Future for Our Past.” In 1981, they opened the Beaches Museum.

Author James A. Michener, Jean Haden McCormick, J.T. McCormick (1981)

It takes a certain kind of person to pull together such a great achievement through sheer force of will. But looking over her life, it is easy to see how well-suited Jean McCormick was to the task. Jean loved Beaches history because she had lived Beaches history. She managed the Oceanic Hotel where she later discovered German spies likely stayed there, disguised as vacationing artists who were only walking the coastline in search of information. The FBI later visited, investigating their suspicion that those long ocean-side walks were taken with the purpose of mapping the coast for a landing and attempted infiltration by Nazi saboteurs in Ponte Vedra during World War II. Jean later oversaw the preservation of the wild invasion story with a historical marker in Ponte Vedra Beach.

Jean was also part of the foundation of many local institutions. Jean was in the second graduating class at Fletcher High School. She was the first bride to walk down the aisle at Beach United Methodist Church. These experiences instilled in her the sense of community that inspired the formation of the Historical Society. She has described her passion as “sentimental,” but it is precisely that ability to find meaning in things of the past that has saved Beaches history from being lost to the currents of time.

J. T. & Mrs. McCormick Attending “Saturday in the Park” during Centennial Celebration, museum in background (1984)

It would seem that she always had her keen sense for preservation and resourcefulness. When Jean and her husband moved from Jacksonville Beach to build a home in Ponte Vedra Beach, she salvaged timbers from her family’s Oceanic Hotel to use for construction. When the Beaches Museum opened in 1981, everything was donated. When the locomotive was acquired, the transport and construction was all fundraised.

She had long possessed the qualities of a leader. As a hobby, Mrs. McCormick was fond of constructing miniatures of homes and buildings. She would build them to scale and curate them with a meticulous attention to detail and loyalty to authenticity. Those same attributes were apparent in her leadership over the foundation and administration of the Beaches Area Historical Society.

In 2006, when the expanded Beaches Museum was completed, Jacksonville Beach Mayor Fland O. Sharp recognized Jean McCormick’s contributions by proclaiming March 7, 2006 to be Jean Haden McCormick Day. Following her recent passing and with that date only weeks away, we ask you to join us in remembering the life and accomplishments of Jean McCormick for Women’s History Month. The Mother of Beaches History—without her, our past would have been washed away by the waves.

In lieu of flowers, the McCormick family has requested that gifts may be made to the Jean McCormick Founders’ Fund at the Beaches Museum. This fund will help to ensure the lasting legacy of Jean McCormick. To donate online, please click here. Thank you.

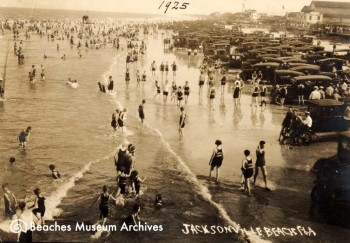

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.  The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.

The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.