This article was written by Fall 2018 Beaches Museum intern, Alex Morales.

After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922.

After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922.

Before breaking flight records, Doolittle was a flying instructor with the Army Air Service in Eagle Pass, Texas where he performed border patrol duties. After years of planning, Doolittle prepared his military issued DeHaviland plane to withstand the long distance flight across the U.S. He stripped it of excess weight so it could support a 285 gallon fuel tank and still remain light. On August 6, 1922, at Pablo Beach (present-day Jacksonville Beach), a large crowd of well-wishers and spectators gathered to see him take off. As his plane taxied across the beach, it got caught in soft sand making it veer into the ocean.

Although embarrassed by the faux pas, Doolittle made the necessary repairs to his plane to try again. On September 4, 1922 at 10 pm, with just kerosene lanterns to illuminate the beach, Doolittle soared into the skies and into history. Twenty-one hours and nineteen minutes later, he touched down in San Diego and broke the transcontinental flight record. Making only one stop in San Antonio, he averaged a speed of 105 miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet.

miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet.

Pablo Beach figured greatly in aviation history due to its location. The distance between San Diego and Pablo Beach is the shortest transcontinental route—a distance of 2,270 miles. The southern route contained fewer mountain ranges and provided relatively better weather conditions for flying. With more military bases along the route, it also ensured that pilots had more opportunities to land safely, refuel, or to seek assistance and shelter in emergency situations. Additionally, beaches served as a prime location for airplanes as the long stretches of sandy shoreline provided an area for pilots to land and take off.

Before Doolittle, Robert Flowler’s flight on October 20, 1911 was the first southerly coast-to-coast flight to land in Pablo Beach. His endeavor took 115 days. Albert D. Smith and his group took 18 days to land in Pablo Beach in 1918. The following year, Major J. T. McCauley flew from coast to coast in 25 hours and 45 mins. Two years later in 1921, Lt. William DeVoe Coney landed in Pablo Beach from San Diego i n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

After making aviation history, Doolittle went on to become a Lieutenant General in the United States Air Force. On April 18, 1942, he and his crew, the Doolittle Raiders, flew 16 bombers leading the first surprise raid on Tokyo. His actions during WWII earned Doolittle military distinctions.

Years later, the Beaches Area Historical Society sought to commemorate the military hero for his role in the history of Jacksonville Beach. On September 4, 1980, the Society invited Lt. Gen. Doolittle back to Jacksonville Beach to unveil and dedicate a marker honoring his historic flight in 1922. The marker continues to stand tall in the Museum’s history park.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.

After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922.

After planes were used during the Great War for air-to-air combat, surveillance, and mail carriers, many U.S. pilots began using their skills to push the limits of aviation technology. Some modified their aircrafts to perform in stunt shows. Others, like Charles Lindberg seized the opportunity to create distance and time records. However, he was neither the only pilot nor the first to make a mark in the aeronautical history books. Jacksonville Beach played host to one famous record breaking pilot, Lt. James H. Doolittle, who set a new transcontinental flight record in 1922. miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet.

miles per hour and stayed at an altitude of 3,500 feet. n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

n 22 hours and 27 minutes.

word of mouth, letters amongst friends, running newspaper articles, as well as networking with other historical preservation groups and city council members. Likewise, the Society became heavily involved in local community activities. The April Opening of the Beaches parade signaled an early turning point for the Society. With a massive community turnout, an unexpected explosion of a nearby buggy during the parade ignited community awareness of the Society. Mr. Charles Cook Howell, Jr. wrote in a small note to Mrs. McCormick stating, “a true Champion has started the society off with a bang! This certainly argues well for the future.”

word of mouth, letters amongst friends, running newspaper articles, as well as networking with other historical preservation groups and city council members. Likewise, the Society became heavily involved in local community activities. The April Opening of the Beaches parade signaled an early turning point for the Society. With a massive community turnout, an unexpected explosion of a nearby buggy during the parade ignited community awareness of the Society. Mr. Charles Cook Howell, Jr. wrote in a small note to Mrs. McCormick stating, “a true Champion has started the society off with a bang! This certainly argues well for the future.” not stop them from putting one together. They utilized two small spaces in the Ocean State Bank and Beaches Guaranty Bank to display two exhibits “full of Memorabilia” that even included a 100,000 year old mammoth tooth.

not stop them from putting one together. They utilized two small spaces in the Ocean State Bank and Beaches Guaranty Bank to display two exhibits “full of Memorabilia” that even included a 100,000 year old mammoth tooth. appropriately named it Pablo Historical Park after Jacksonville Beach’s previous name. The park eventually became home to five “at risk” structures, items, memorials, and markers representing and celebrating the bygone era of the Beaches Area. However, the addition of the Beaches Museum and History Center in 2006 ushered a new phase of the Society’s role in the community.

appropriately named it Pablo Historical Park after Jacksonville Beach’s previous name. The park eventually became home to five “at risk” structures, items, memorials, and markers representing and celebrating the bygone era of the Beaches Area. However, the addition of the Beaches Museum and History Center in 2006 ushered a new phase of the Society’s role in the community. Jacksonville Beach. Located on Beach Blvd at the Beaches Museum & History Park, the garden, a Duval County Extension Demonstration Garden, is maintained by Master Gardener volunteers with the purpose of community education in gardening practices.

Jacksonville Beach. Located on Beach Blvd at the Beaches Museum & History Park, the garden, a Duval County Extension Demonstration Garden, is maintained by Master Gardener volunteers with the purpose of community education in gardening practices.

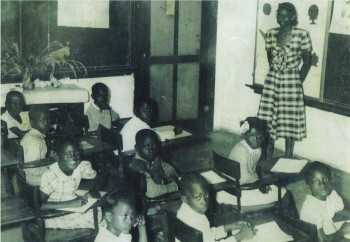

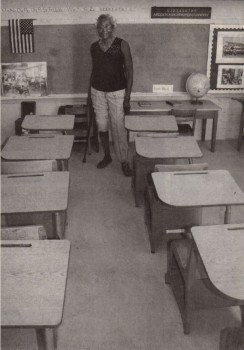

Orpah Jackson was, and continues to be, an important member of the Beaches community; working as a teacher for 55 years and actively participating in community projects. Born on June 15th, 1920 in Lumpkin, Georgia, her family later moved to a small neighborhood in East Mayport, Florida when she was 6 years old. This move was influenced by her mother’s desire to provide a better education for Orpah and her brother.

Orpah Jackson was, and continues to be, an important member of the Beaches community; working as a teacher for 55 years and actively participating in community projects. Born on June 15th, 1920 in Lumpkin, Georgia, her family later moved to a small neighborhood in East Mayport, Florida when she was 6 years old. This move was influenced by her mother’s desire to provide a better education for Orpah and her brother. In 1946 she moved back to Duval County and began a job as teacher and principal of 19 African American students in Mayport Village. When that school was closed in 1948, she began teaching 2nd grade at School #144 in Jacksonville Beach. Here, Orpah taught a wide range of subjects to her 2nd graders including reading, math, music, and physical education for 20 years.

In 1946 she moved back to Duval County and began a job as teacher and principal of 19 African American students in Mayport Village. When that school was closed in 1948, she began teaching 2nd grade at School #144 in Jacksonville Beach. Here, Orpah taught a wide range of subjects to her 2nd graders including reading, math, music, and physical education for 20 years. Orpah was involved with many projects including the coordination of the integrated Vacation Bible School for the local churches, working with Meals on Wheels as a member of Church Women United, providing assistance to the neighborhood through the Donner Community Development Corporation, and serving as the first African American woman in Atlantic Beach to work on the voting Precinct. She currently serves as a member and Treasurer on the Board of the Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Heritage Center, which works to preserve the history of School #144 where her old classroom is on display.

Orpah was involved with many projects including the coordination of the integrated Vacation Bible School for the local churches, working with Meals on Wheels as a member of Church Women United, providing assistance to the neighborhood through the Donner Community Development Corporation, and serving as the first African American woman in Atlantic Beach to work on the voting Precinct. She currently serves as a member and Treasurer on the Board of the Rhoda L. Martin Cultural Heritage Center, which works to preserve the history of School #144 where her old classroom is on display.

The Beaches Museum & History Park’s Board of Directors started its 2017-2018 year strong with the presentation of its new Strategic Plan. The 10-month process was supported by the Community Foundation and was facilitated by Jana Ertrachter, the Ertrachter Group, who brought years of experience guiding organizations through the Strategic Planning Process.

The Beaches Museum & History Park’s Board of Directors started its 2017-2018 year strong with the presentation of its new Strategic Plan. The 10-month process was supported by the Community Foundation and was facilitated by Jana Ertrachter, the Ertrachter Group, who brought years of experience guiding organizations through the Strategic Planning Process. Rush Abry, a well-known Beaches photographer, managed to capture the only image of the crash site after wading through chest-high water to reach a tiny island where the patrol plane crashed and burned upon impact. His stunning black-and-white photo of four first-responders straddling the plane’s crumpled fuselage as a fire blazes behind them won a state press award for on-the-spot photography.

Rush Abry, a well-known Beaches photographer, managed to capture the only image of the crash site after wading through chest-high water to reach a tiny island where the patrol plane crashed and burned upon impact. His stunning black-and-white photo of four first-responders straddling the plane’s crumpled fuselage as a fire blazes behind them won a state press award for on-the-spot photography. The unique and memorable buildings of Atlantic Beach have greatly contributed to the character of this community throughout its life. The Continental Hotel – a monumental structure built at a time when there were almost no other buildings around – set the tone for the future of the community. The people who shaped Atlantic Beach in its early days hoped to form a more upscale community that drew in more elite residents. From converted carriage houses to a “hobbit house,” this trend has led to some of the most unique structures in the Beaches communities. The buildings mentioned below are just a few examples of the architecture found in Atlantic Beach throughout the years.

The unique and memorable buildings of Atlantic Beach have greatly contributed to the character of this community throughout its life. The Continental Hotel – a monumental structure built at a time when there were almost no other buildings around – set the tone for the future of the community. The people who shaped Atlantic Beach in its early days hoped to form a more upscale community that drew in more elite residents. From converted carriage houses to a “hobbit house,” this trend has led to some of the most unique structures in the Beaches communities. The buildings mentioned below are just a few examples of the architecture found in Atlantic Beach throughout the years. The Bull House. Built around 1902, this house represented some of the earliest construction in Atlantic Beach. The home of several members of the Bull family over the years, it was a longtime landmark in Atlantic Beach.

The Bull House. Built around 1902, this house represented some of the earliest construction in Atlantic Beach. The home of several members of the Bull family over the years, it was a longtime landmark in Atlantic Beach.

Abri. This Italian Renaissance Revival style house built around 1934 was originally owned by Broadway legend Lawrence Haynes. In his autobiography, “Joyous Life of a Singer”, Haynes attributes the name to a phrase used in World War I: “Vite a L’Abri,” which meant “Quick to the place where we are safe – where no harm can reach us.”

Abri. This Italian Renaissance Revival style house built around 1934 was originally owned by Broadway legend Lawrence Haynes. In his autobiography, “Joyous Life of a Singer”, Haynes attributes the name to a phrase used in World War I: “Vite a L’Abri,” which meant “Quick to the place where we are safe – where no harm can reach us.”

When discussing golf in the Beaches area, most will look towards Ponte Vedra Beach, particularly TPC Sawgrass and the annual PLAYERS Championship. However, Atlantic Beach has its own storied history in the world of golf.

When discussing golf in the Beaches area, most will look towards Ponte Vedra Beach, particularly TPC Sawgrass and the annual PLAYERS Championship. However, Atlantic Beach has its own storied history in the world of golf. The Selva Marina Country Club, a project initiated by Harcourt Bull, Jr., opened in 1958. Well received in the area, it featured a golf course designed by E. E. Smith and quickly grew to include tennis courts, a swimming pool, and a residential community. Selva Marina soon became an important and internationally recognized part of the community. It is best remembered as the birthplace of the Greater Jacksonville Open in 1965. Years later, this tournament became what is now known as the PLAYERS Championship. Playing host to many of golf’s greatest players including Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, Selva Marina created a name for itself in golf history. The Lady Jacksonville Open was also held at Selva Marina in 1975.

The Selva Marina Country Club, a project initiated by Harcourt Bull, Jr., opened in 1958. Well received in the area, it featured a golf course designed by E. E. Smith and quickly grew to include tennis courts, a swimming pool, and a residential community. Selva Marina soon became an important and internationally recognized part of the community. It is best remembered as the birthplace of the Greater Jacksonville Open in 1965. Years later, this tournament became what is now known as the PLAYERS Championship. Playing host to many of golf’s greatest players including Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, Selva Marina created a name for itself in golf history. The Lady Jacksonville Open was also held at Selva Marina in 1975. Today, the new Atlantic Beach Country Club continues Atlantic Beach’s golfing legacy at the site of old Selva Marina Country Club. In addition to the 6,815 square foot course redesigned by Erik Larsen, Atlantic Beach Country Club currently includes a neighborhood with 178 homesites, tennis courts, fitness facility, a junior Olympic swimming pool, and a 16,000 square foot clubhouse. Opened in January 2015, the revitalized 18-hole course was named as one of the nation’s Best New Courses by Golf Digest Magazine in 2014. The Web.com Tour Championship, part of the PGA TOUR, will be held at ABCC in Fall 2017.

Today, the new Atlantic Beach Country Club continues Atlantic Beach’s golfing legacy at the site of old Selva Marina Country Club. In addition to the 6,815 square foot course redesigned by Erik Larsen, Atlantic Beach Country Club currently includes a neighborhood with 178 homesites, tennis courts, fitness facility, a junior Olympic swimming pool, and a 16,000 square foot clubhouse. Opened in January 2015, the revitalized 18-hole course was named as one of the nation’s Best New Courses by Golf Digest Magazine in 2014. The Web.com Tour Championship, part of the PGA TOUR, will be held at ABCC in Fall 2017.