Operation Pastorius

Under the cover of night, four Nazi spies departed from a submarine just off the coast of Florida. Upon landing, they concealed explosive materials and other items in the sand, and disappeared into the unsuspecting beachfront community with intentions of sabotaging American war efforts. While it may sound like another sensational and fictional World War II story from Hollywood, it happened during the late night hours of June 16, 1942 here on Ponte Vedra Beach.

Spies have long been utilized by opposing sides during wartime, and World War II was by no exception. Operations like these were already underway by the Nazis before the United States entered the war. After America declared war on Germany in December 1941 in the wake of Pearl Harbor, German interest in infiltrating the country increased greatly. By the summer of 1942, one such mission known as Operation Pastorius was already under way. The main objective of this mission was to create a crippling disruption of production of war materials in the United States; specifically aiming at aluminum and magnesium plants.

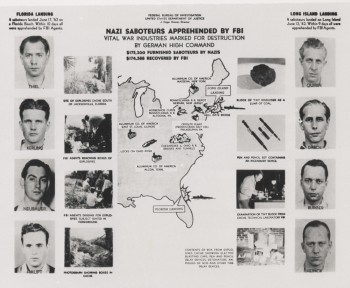

Armed with extensive training on sabotage, particularly in the creation and utilization of explosives, two groups of four men were sent to the Eastern coast of the United States. The first group, which landed in Long Island, NY, included George John Dasch, Ernest Peter Burger, Heinrich Harm Heinck and Richard Quirin; the second group, which landed in Ponte Vedra Beach, included Edward John Kerling, Werner Thiel, Hermann Otto Neubauer and Herbert Hans Haupt.

Ponte Vedra Beach was chosen as the site of the second landing as it was already known to the leader of that group, Kerling. In fact, all of these men had one very important factor in common: they had all lived for some time in the United States prior to this mission. They were chosen specifically for this reason since they were already familiar with American society and would be able to blend in easily among the crowds without arousing suspicion.

The second group arrived on the shores of Ponte Vedra Beach by submarine, also known as a U-boat, during the late night hours of June 16. The four spies were brought ashore in collapsible rubber boats, which were then rowed back to the submarine. Now left to their own devises, the four quickly hid their explosives and money in the sand among the palm trees and left with the intention of returning for these items within a few days.

At left, FBI agents dig in the dunes near the saboteur’s landing site in Ponte Vedra Beach. Below, raw materials for making bombs discovered by the agents.

However, they did not count on being discovered before their return. Within a few days of landing at Long Beach, members of the group in New York were arrested and the plot was soon revealed. Though they had already left the state of Florida, the other spies were quickly captured and newspapers across the nation were soon filled with the trial regarding the fate of the spies. The trial concluded with death sentences for six of the saboteurs except for Dasch and Burger, who agreed to provide information in exchange for lesser sentences. Burger was given a life sentence in prison while Dasch received 30 years. He later went on to write a book about the story entitled Eight Spies Against America in 1959.

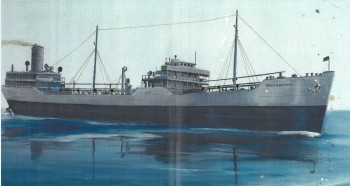

After the news was spread, beachfront security in the Beaches area was tightened, particularly in the strip of land where the saboteurs had landed. This incident and the sinking of the SS Gulfamerica oil tanker ensured a ban on lights along the shore front throughout the rest of the war.

The night of April 10, 1942 started as a typical Friday night for people in the Beaches area. Jacksonville Beach was teeming with crowds kicking off their weekend with a visit to the boardwalk amusements, attending a dance at the pier, or catching the latest movie at the local theater. At approximately 10 p.m., however, the night took a very different turn.

The night of April 10, 1942 started as a typical Friday night for people in the Beaches area. Jacksonville Beach was teeming with crowds kicking off their weekend with a visit to the boardwalk amusements, attending a dance at the pier, or catching the latest movie at the local theater. At approximately 10 p.m., however, the night took a very different turn.

The Continental Hotel, constructed on the oceanfront in Atlantic Beach, opened in June of 1901. While it still featured luxury accommodations like Flagler’s other Florida resorts, it was simpler in design than hotels like the Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine. The hotel featured its own golf course, a detached veranda that wrapped around the hotel for lounging, an 800 foot ocean pier—the Atlantic Beach Pier—for fishing, picturesque drives around the area, and automobiling (racing) along the shore. Stretching along the oceanfront at 447 feet long and 47 feet wide, the wooden hotel provided a grand and palatial figure at the Atlantic Beach seashore. The building was yellow—a specific shade used by the FEC—with green shutters, accommodations for over 200 people, and a dining room that could seat 350 people. In advertisements for the hotel, the building was described as having an architectural design which was “perfectly balanced and pleasing to the eye” with its symmetry.

The Continental Hotel, constructed on the oceanfront in Atlantic Beach, opened in June of 1901. While it still featured luxury accommodations like Flagler’s other Florida resorts, it was simpler in design than hotels like the Ponce de Leon in St. Augustine. The hotel featured its own golf course, a detached veranda that wrapped around the hotel for lounging, an 800 foot ocean pier—the Atlantic Beach Pier—for fishing, picturesque drives around the area, and automobiling (racing) along the shore. Stretching along the oceanfront at 447 feet long and 47 feet wide, the wooden hotel provided a grand and palatial figure at the Atlantic Beach seashore. The building was yellow—a specific shade used by the FEC—with green shutters, accommodations for over 200 people, and a dining room that could seat 350 people. In advertisements for the hotel, the building was described as having an architectural design which was “perfectly balanced and pleasing to the eye” with its symmetry. Margaret McQueen was a lifelong advocate for residents of the Beaches community and the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council. She was born February 5, 1940, in Jacksonville Beach, Florida. In 1958, McQueen moved to Indiana where she started a family and returned to the Beaches area in 1969. Newly divorced and the mother of four, McQueen enrolled at the University of North Florida and graduated in 1974 with a degree in education. As a mother and second grade teacher at Seabreeze Elementary School, McQueen saw the issues of drugs, crime, and poverty eroding the Beaches neighborhoods. In 1989, she lead the Jacksonville Beach Community Action Co-op to address community issues of crime and to further increase the cooperative partnership between citizens and police.

Margaret McQueen was a lifelong advocate for residents of the Beaches community and the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council. She was born February 5, 1940, in Jacksonville Beach, Florida. In 1958, McQueen moved to Indiana where she started a family and returned to the Beaches area in 1969. Newly divorced and the mother of four, McQueen enrolled at the University of North Florida and graduated in 1974 with a degree in education. As a mother and second grade teacher at Seabreeze Elementary School, McQueen saw the issues of drugs, crime, and poverty eroding the Beaches neighborhoods. In 1989, she lead the Jacksonville Beach Community Action Co-op to address community issues of crime and to further increase the cooperative partnership between citizens and police. In 1991, at the age of 51, McQueen ran for the District 1 City Council seat. The election included the first ever district voting, which divided voters into geographic districts to choose their candidates. The District 1 City Council seat included the central and northeast sections of Jacksonville Beach, encompassing the same area where McQueen lived and raised her family. McQueen became the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council on November 5, 1991, thus marking a historic moment for the Beaches community. She diligently served on the City Council from 1991 through 1994 and again in 1998. During that time, she saw the needs of the community improved. On June 29, 2013, McQueen passed away at the age of 73.

In 1991, at the age of 51, McQueen ran for the District 1 City Council seat. The election included the first ever district voting, which divided voters into geographic districts to choose their candidates. The District 1 City Council seat included the central and northeast sections of Jacksonville Beach, encompassing the same area where McQueen lived and raised her family. McQueen became the first African American elected to the Jacksonville Beach City Council on November 5, 1991, thus marking a historic moment for the Beaches community. She diligently served on the City Council from 1991 through 1994 and again in 1998. During that time, she saw the needs of the community improved. On June 29, 2013, McQueen passed away at the age of 73. The legacy of McQueen included the positive change one woman brought to her community through her efforts of grassroots organizing and civic engagement. She brought equal representation to her district and stood firm in her convictions for the belief in the greater good not just of her community, but for all the surrounding communities of the Beaches. She strove to make the Beaches a better place to live and spearheaded the volunteerism of both blacks and whites. The Beaches community is forever grateful for the contributions and leadership of women such as Margaret McQueen.

The legacy of McQueen included the positive change one woman brought to her community through her efforts of grassroots organizing and civic engagement. She brought equal representation to her district and stood firm in her convictions for the belief in the greater good not just of her community, but for all the surrounding communities of the Beaches. She strove to make the Beaches a better place to live and spearheaded the volunteerism of both blacks and whites. The Beaches community is forever grateful for the contributions and leadership of women such as Margaret McQueen.