Cut Down in his Prime

Former Fletcher football star died at mysterious Texas Army base in 1954.

By Johnny Woodhouse

Faye Mickler Farace was curling her eyelashes in the girl’s bathroom at Fletcher High when one of her classmates burst in and said, “Oh, you have see this new guy, but I’m going to get him first.”

The “new guy” was Charles Harby “Buddy” Page Jr., a handsome transfer student from Landon High who had just moved to the Beaches in the fall of 1951.

“He was very good looking. I mean he was perfect,” recalled Farace, now 89. “All the girls were crazy about him. He dated a girlfriend of mine before he eventually asked me out at the end of our junior year. From then on, we started making our plans.”

New kid on the block

A gifted athlete, Page quickly caught the eye of Fletcher High athletic coaches, including football coach Ish Brant, who was coming off a 7-2-2 season in 1950.

Brant was always on the lookout for fleet-footed halfbacks to buoy his T-formation offense and the 6-foot-tall, 165-pound Page fit the bill.

“He worked out with weights long before any of us did,” recalled Lee Buck, who played with Page on Fletcher’s 1951 and 1952 football squads. “He was very muscular and would literally bounce off tacklers.”

Page broke into Fletcher’s starting football lineup midway through his junior year. The following spring, he helped the Senators win the 1952 Class A state track title as a point-scoring sprinter and relay runner.

Off the playing field, Page bonded with the likes of Tommy Hulihan, Henry “Preacher” Stout, Stacy Barber and Buck, all members of the Class of 1953.

“Tommy’s house on Laura Street [in Neptune Beach] was our meeting place,” said Buck. “His mother treated us like we were her own sons.”

“We were all very close,” added Farace, a former Fletcher majorette and Homecoming Queen. “Tommy and Buddy were the best of friends. It was a wonderful time back then. About the worst thing we did was smoke cigarettes.”

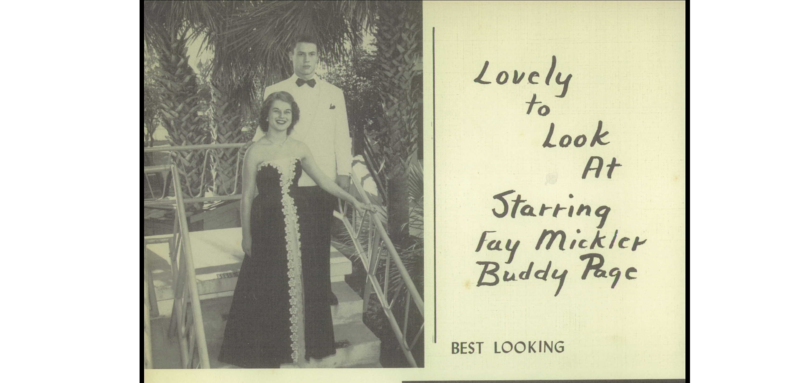

In 1953, Page and Farace were voted “Best Looking” in the yearbook.

“I wonder if that’s Fay Mickler driving up to the theater in that big limousine. She’s quite a celebrity with her titles of Miss America and Mrs. Charles Page Jr., that famous professional football player,” the yearbook’s “class prophecy” section predicted.

Big man on campus

Fletcher opened the 1952 football season with a dominating 33-18 victory over Live Oak Suwanee. Page scored the game’s opening touchdown to get the visiting Senators rolling. It would be the first of nearly a dozen TD runs for the speedy senior halfback whose name and image appeared in sports pages on a regular basis.

“Page is fleet of foot and capable of getting away for sizeable gains,” wrote sportswriter Rocco Morabito of the Florida Times-Union before Fletcher’s first home game of a season, a 35-6 triumph over visiting Miami Tech.

A photo and caption proclaiming Page a “breakaway threat” appeared in the T-U sports pages, leading up to Fletcher’s game with Clearwater Central Catholic.

Heading into the season finale against Lake City on Dec. 14, 1952, Brant, Fletcher’s silver-haired head coach, told a T-U sportswriter, “Page offers a terrific backfield threat and if we need one or two yards, he’ll blast in there and get it.”

A week before the Lake City game, which was played at the Gator Bowl, Page and teammate Larry Adams, Fletcher’s top scorer and leading pass catcher, were both offered football scholarships to the University of Florida.

Adams (70 points) caught more than 10 TD passes for the Senators in 1952 and handled all the punting and extra-point kick duties.

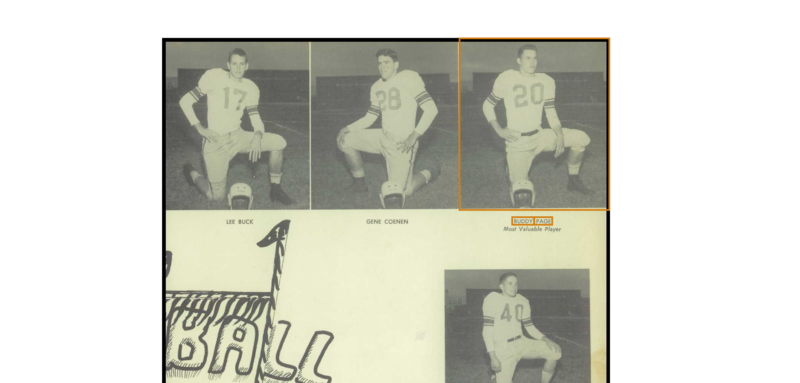

Page (66 points), who averaged 8.5 yards per carry during the regular season, was Fletcher’s most valuable player.

“Coach Ish Brant is high in his praise of both boys, and feels they had a heavy hand in helping his team to a 9-2 season, the best record Fletcher ever has posted,” The Jacksonville Journal reported.

One final football fling

In mid-August 1953, Page and Adams, along with Fletcher’s Bert Bibby and John Veal, participated in the North-South All-Star Game at the Gator Bowl. The fifth annual event featured many of the best football players in the state, including Miami quarterback Lee Corso, who led the South All-Stars to a 33-6 win.

Adams caught an 18-yard pass in the game and Page was photographed carrying the ball while being chased by a pair of would-be tacklers. “The crowd was brought to its feet in the second quarter of last night’s all-star game as the North’s Buddy Page picked up eight years around left end,” a T-U photo caption read.

Page and Adams split up after the all-star game, with Adams heading off to play for the University of Florida and Page signing with in-state rival Florida State University.

When Page arrived in Tallahassee for the first day of drills on Aug. 24, 1953, FSU’s incoming freshmen class was considered “the best crop of newcomers ever lined up for the Seminoles.” In a team photo, Page is pictured sitting next to Fletcher grad Jimmy Messinese, one of FSU’s 34 returning lettermen.

Messinese, a backup linebacker, and Fletcher grad George Boyer, a starting defensive tackle, appeared in numerous games for FSU in 1953, but Page apparently left school before the football season began.

“His parents were pushing him to stay in college, but Buddy made up his mind to go into the Army,” Farace recalled. “His plan was to serve for two years and then play football for the University of Florida. He said we could live in some Quonset huts on campus that were reserved for married couples.”

Newly-minted MP

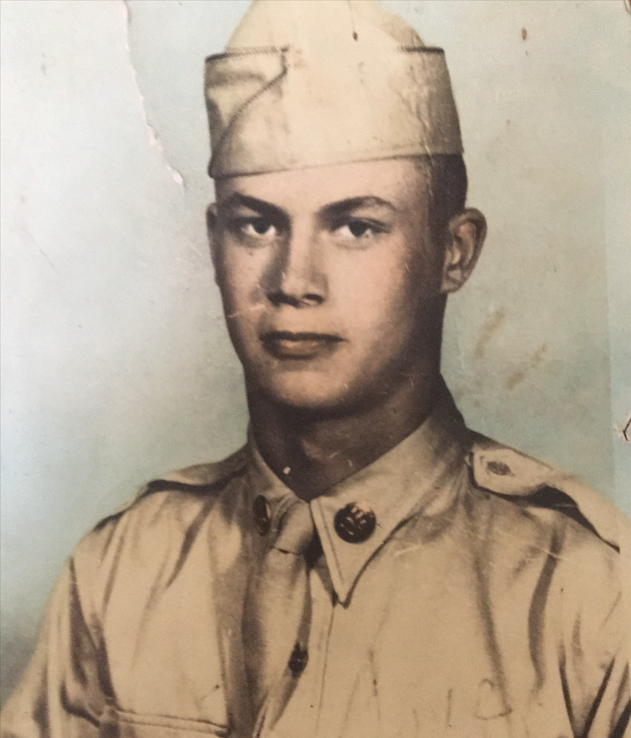

Page enlisted in the Army on Sept. 17, 1953, and completed basic training at Camp Gordon (now Fort Eisenhower) near Augusta, Georgia. From 1948-1975, Camp Gordon was home to the Army’s Military Police School.

After graduating from boot camp, Page was selected to attend 16 weeks of MP training at Camp Gordon’s Provost Marshal General Center. The training included eight weeks of advanced infantry tactics and eight weeks of training in the duties and techniques of being a military policeman.

“MPs are among the best trained, best uniformed and sharpest soldiers in the United States Army, and ready to answer the call from whatever spot on the globe it might come,” proclaimed a black-and-white training film produced at Camp Gordon in 1953.

For Page, answering the call meant reporting to the 8455th Military Police Company at Killeen Base, a remote Army installation in central Texas and one of three sites in the country for the storage and assembly of nuclear weapons during the early years of the Cold War.

“I remember driving up to Camp Gordon with Buddy’s parents, Harby and Roberta Page,” said Farace. “Once Buddy got to Killeen, we never saw him again.”

Code name Site Baker

In 1947, Killeen Base, now known as Fort Cavazos and before that Fort Hood, was one of several ideal spots to store the nation’s nuclear arsenal, according to The Fort Hood Herald. “The idea was (the sites) were built inland to a point where, at the time, the Soviet Union didn’t have the capability to reach in and attack,” said Charles Lauer, formerly director of the Fort Hood Underground Training Facility, which once housed the atomic bomb.

According to Lauer, military personnel stationed at Killeen Base were forbidden to enter parts of the facility under Atomic Energy Commission control. “At the time, when the country’s nuclear arsenal was in its infancy and bombers were the only reliable delivery system, Killeen Base operated on a complex set of protocols,” Lauer said.

Dotted with ammunition bunkers, concrete guard towers and razor-wire fences, Killeen Base, also known by its code name Site Baker, was off limits to visitors and area residents. “Security was extremely tight, producing many stories and rumors about what went on inside,” according to another published report.

One rumor involved a couple of deer hunters who accidentally strayed onto the base. The hunters were reportedly arrested by MPs and held until it was determined that they were not communist spies.

“The only way you can leave here is if you go crazy or shoot someone and then they ship you out,” Page told Farace in a 1954 letter. “I can’t leave this base no matter what. I won’t leave here until I’m out of the Army.”

When Page arrived at Killeen Base in January 1954 at age 18, he quickly learned that leaves were rarely granted, and transfers were out of the question.

“I went to the CO about going into the Airborne, but found out I couldn’t,” he told Farace in another letter. “The most important thing to me is having you with me, so let me know when you want to get married. I will start working things out. Let me know what kind of ring you want or if you want to wait until I come home. Love you forever, Buddy.”

Cut down in his prime

On July 1, 1954, a U.S. Army plane crashed during a training flight at Kelly Air Force Base, in San Antonio, Texas, killing two men, including John McBride, a 20-year-old student pilot and a promising running back who played on Alabama’s 1953 Southeastern Conference championship team.

Page, who turned 19 on Feb. 3, 1954, was also cut down in his prime that July after being fatally shot while on vehicle patrol in a classified area of Killeen Base.

According to a newspaper report, Page, who was riding as a passenger in a patrol vehicle, was shot in the chest by a sentry on July 4, 1954, after allegedly failing to answer the sentry’s challenge.

“The deceased fell from the vehicle and died shortly thereafter approximately 20 feet from the vehicle,” a report said. The MP driving the patrol vehicle was not injured. At the time, military officials said the sentry would be court martialed.

When he was shot, Page was dressed in Army fatigues and carrying only a pocketknife and an MP whistle, according to medical records.

“Buddy reportedly told the guard, ‘You know who I am,’ but the guy still shot him,” said Buck. “His death was such a shock and a senseless waste of life.”

A nightmare that lingers

Farace was returning home from a trip to Daytona Beach when the tragic news reached her.

“My mother met me outside our home on Mickler Road and said, ‘Buddy has been killed.’ I don’t remember much after that,” Farace recalled. “Somebody took me to Buddy’s house, and I stayed in a spare bedroom for a couple of days waiting for the train to bring his body back to Jacksonville. To this day, I don’t know how we got through it.”

Two MPs from Page’s unit, Pfc. James L. Morris and Sgt. Clarence E. Van Nest, accompanied the steel casket to the Jacksonville train station and served as official military escorts during the funeral. Buck said he and some of Page’s closest friends took turns standing vigil at the funeral home after Page’s remains were prepared for viewing.

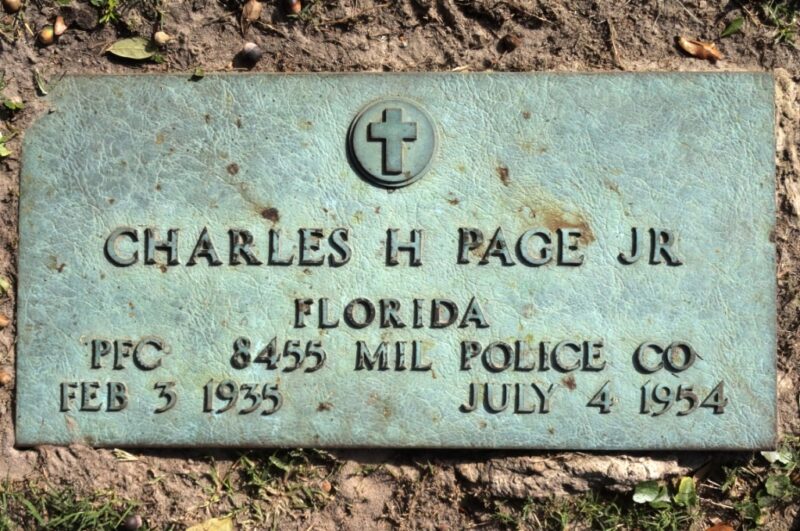

A memorial service was held a few days later with the Rev. Malcolm B. Knight, pastor of Southside Baptist Church, and the Rev. Henry Stout of Community Presbyterian Church in Atlantic Beach, presiding. Page’s remains were buried at Jacksonville’s Oaklawn Cemetery with full military honors.

Four days after Page was killed, U.S. Sen. George A. Smathers of Florida requested a full investigation of the shooting. “Smathers said he acted immediately after receiving the request from Page’s father,” according to a front-page article in the Florida Times-Union. “Sen. Smathers said he has also called the Judge’ Advocate General’s Office and was assured by Major Gen. Albert C. Smith that the investigation would be followed through by that office,” the newspaper said.

On June 28, 1955, U.S. Rep. Charles Bennett of Jacksonville introduced a bill (H.R. 7074) in the U.S. House of Representatives “for the relief of Mr. and Mrs. Charles H. Page” in the sum of $25,000.

The bill was referred to the House’s Judiciary Committee and forwarded to the Office of the Quartermaster General, which was directed to prepare a report for Congress.

In March 1967, Bennett’s bill was finally passed in the U.S. House and sent to the U.S. Senate for consideration. By then, the death benefit had been reduced to $14,430, according to published reports.

It’s unclear whether Page’s parents ever saw any compensation. Roberta Page died in 1969, the same year Killeen Base was officially decommissioned as a nuclear storage bunker. Charles Harby Page Sr., who worked for the U.S. Corps of Engineers, passed away in 1973.

“Buddy’s parents never accepted the Army’s explanation for what happened to their son,” Buck said. “His death destroyed them. He was their whole life.”

Farace, who went on to marry twice and has seven children and 10 grandchildren, keeps a portrait of Page in a dresser drawer.

“Even after Buddy was gone, his parents would continue to visit me and my parents,” Farace said. “My parents adored Buddy. His death was a nightmare for all of us.”