Casa Marina – the Jewel of the Beaches

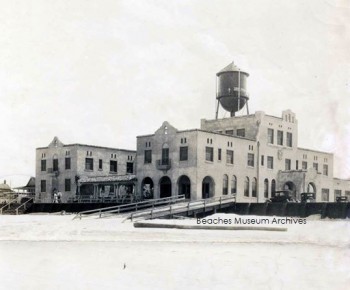

The Casa Marina Hotel and Restaurant opened on June 6, 1925. The hotel had 60 rooms, each with a closet, telephone, hot and cold water and a connecting bath with tub or shower. It cost $150,000 for the building and furnishings, it was exquisite!

“The new Casa Marina is perhaps one of the finest hotels of its size in the South,” boasts an article in the June 6, 1925 issue of the Pablo Beach News. “The $150,000 seaside resort is ideally located, being in the heart of beach activities.” Two hundred guests attended its opening that same day, dining and dancing until one o’clock in the morning.

Under the management of Gene Zapf – a popular restaurateur, city-council member, and banker – the 60-room hotel was an instant hit with locals and out-of-towners. The likes of John D. Rockefeller, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Jean Harlow, and Al Capone are rumored to have been guests during its early years.

Guests spent their days on Jacksonville Beach, the most exciting tourist town in northeast Florida. It had a boardwalk, dancing, casinos, amusement rides and wide beaches. At night guests dined and danced in the elegant ‘salon’ at the Casa Marina.

The Great Depression sent the Roaring 20s and an already-fading tourism industry packing. The Forties were very different for the Casa Marina. The US government leased the property in 1944 for seven years to house Naval Officer’s families and war workers stationed at Mayport.

Afterward, it was plagued by a series of foreclosures, sales, and well-intentioned plans. Not until 1991 did it begin its journey back to its former glory. After millions in renovations, The Casa Marina Hotel– as it did nearly one hundred years ago – offers luxury accommodations, fine dining, and entertainment in Jacksonville Beach once again.

“The Casa Marina has endured a lot. She has been remodeled, repainted and expanded. Restaurants and shops have come and gone. The hotel enjoyed financial success, bankruptcy, closure and financial success again. The little jewel, the Casa Marina Hotel, persisted.” –Don Mabry

Today, the Casa Marina Hotel & Restaurant offers 23 luxurious bedrooms and parlor suites decorated to represent the distinctive and changing eras of its rich history. The Rooftop has one of the most stunning views of the Florida coastline.

For a more in depth history of the Casa Marina read Don Mabry’s history here.

To make a donation to Beaches Museum in celebration of Casa Marina’s 95th Birthday go here.

![]()

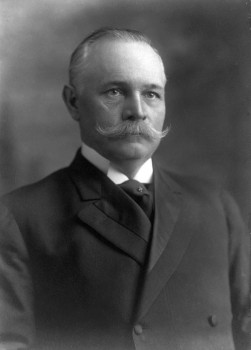

Duncan U. Fletcher Middle and High Schools are landmarks of the Beaches. With so much needed attention focused on the naming of our public schools, I wanted to address the history of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher.

Duncan U. Fletcher Middle and High Schools are landmarks of the Beaches. With so much needed attention focused on the naming of our public schools, I wanted to address the history of Senator Duncan U. Fletcher.

Rhoda L. Martin was born a slave in Abbeville, South Carolina in 1832. In late 1891, she moved to the beaches area as a free woman.

Rhoda L. Martin was born a slave in Abbeville, South Carolina in 1832. In late 1891, she moved to the beaches area as a free woman.

Michener and the McCormicks

Michener and the McCormicks