The Lindbergh Baby Memorial

The Lindbergh Baby Memorial

The Lindbergh Baby Memorial

The Lindbergh Baby Memorial

The Lindbergh Baby Memorial

The St. Johns River Ferry

The St. Johns River Ferry

This article is an excerpt from the 2016 exhibit, Mayport Village: On the River of Change.

Locals and visitors have been crossing the St. Johns River between Fort George Island and Mayport Village for centuries. In the 1600s, Spanish missionaries relied upon those they wished to convert, the Timucua Indians, to provide transport via dugout canoe. In the post-Civil War years, residents, travelers, tradesmen and farmers often crossed the river by way of privately-owned flatboat ferries.

The post-World War II boom in automobile tourism and federally-mandated highway extensions led to a dramatic increase in traffic to Northeast Florida. State and local officials recognized that an uninterrupted coastal highway would not only bolster the economies of seaside communities from Fernandina Beach to St. Augustine but also ease traffic on inland roadways. More than seventeen miles of new highway and a formal ferry service connecting Fort George Island to Mayport Village was required to realize this goal.

On September 15, 1950, the St. Johns River Ferry Service opened to the public. The ferry slips were built 2.5 miles inland from the mouth of the St. Johns River. Inaugural ships, the Reliance and the Monadnock, carried passengers and cars along the 0.9 mile water route connecting North and South State Road A1A.

Billed as “the gateway to A1A,” this newly-created stretch of highway enabled motorists to bypass Jacksonville via the St. Johns River Ferry Service. A marketing campaign invited tourists to travel the “Buccaneer Trail” and “ride through history on Florida A1A.” Suggested stops along the Buccaneer Trail included Fort Clinch, Kingsley Plantation, and Mayport Village for its French Huguenot history and “unsurpassed” seafood supported by the local shrimping fleet.

Locals have fought the closure of the St. Johns River Ferry Service in recent years in the face of state and city budget cuts. In 2016, community advocates and officials successfully secured funding for guaranteed operations for the next two decades. The ferryboat, Jean Ribault–built in 1996–currently supports the St.Johns River Ferry Service with a carrying capacity of 40 cars and 206 passengers. Boasting membership to the East Coast Greenway, the Ferry is now a vital link in a 3,000 mile-long trail system stretching from Maine to South Florida.

Residents gather for the official opening of the St. Johns River Ferry Service. September 16, 1950.

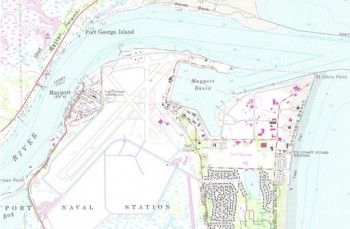

Residents gather for the official opening of the St. Johns River Ferry Service. September 16, 1950. “Mayport Topographical Map, 1964 excerpt”–Excerpt from a 1964 topographical map of the area. The ferry path is traced out on the left.

“Mayport Topographical Map, 1964 excerpt”–Excerpt from a 1964 topographical map of the area. The ferry path is traced out on the left. Early Mayport Village residents, Ethel Spaulding Tuttle (left) and Beatrice Sallas Tuttle (far right), waiting for a ferry. Circa 1900.

Early Mayport Village residents, Ethel Spaulding Tuttle (left) and Beatrice Sallas Tuttle (far right), waiting for a ferry. Circa 1900. Aerial view of the proposed St. Johns River Ferry Service route from July 1950.

Aerial view of the proposed St. Johns River Ferry Service route from July 1950.

Dear Friends:

The mission of the Beaches Museum is to “preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area.” Although the Museum is currently closed, the work of that mission is even more important than ever. We are living tomorrow’s history right now!

To that end, we encourage members of the Beaches community to help us gather information, photos, physical items and first-hand accounts of how you, your family, your business and your community are being impacted. Anything from photos of closed businesses to stories of neighbors helping neighbors will help us compile a thorough accounting of how the Beaches weathered this crisis.

Submissions to our historic record can be sent to archives@beachesmuseum.org.

In addition to working to preserve history as it is made, we are also making more programming available online. Over fifty videos including our Boardwalk Talk Series are now available on our YouTube Channel. We are posting articles, historic photos and more on Facebook and Instagram. We invite and encourage you to take some time to learn a little bit more about the history of our beloved community! Visit beachesmuseum.org to find out more.

Thank you for your support and we look forward to hearing from you as we continue to move our mission forward!

Chris Hoffman

Executive Director

Dear Friends:

The board and staff of the Museum have been monitoring the evolving situation with regards to coronavirus. In an effort to ensure the health and safety of our volunteers, staff and guests, we will be closing the Museum to the public beginning on Tuesday, March 17. We plan to re-open the Museum on March 31.

Additionally, we are postponing the following events:

March 16: Mama Blue concert

March 18: Ritz Chamber Players concert

March 27: “Our Land–Indigenous Northeast Florida” exhibit opening.

We will work to reschedule them as soon as we possibly can. We will send updates on any future cancellations, closures, etc. as we have them.

Thank you for your support and understanding.

Sincerely:

Chris Hoffman

Executive Director

Jean H. McCormick visits with the Blue Angels pilots

Johnny Woodhouse interviewed Roy Voris, the founder of the Blue Angels, prior to the 2003 Sea & Sky Spectacular at Jacksonville Beach. Voris died in 2005.

by Johnny Woodhouse

The Blue Angels, the Navy’s premier flight demonstration squadron, practiced in a cloud of secrecy prior to its first public performance at NAS Jacksonville in 1946. Shunning populated areas such as the Beaches, the unit, then made up of four planes, flew over densely wooded areas west of Jacksonville, performing their “V” and “Echelon” formations in carrier-based Hellcat fighters made famous in World War II.

“The first instruction I got when I formed the Blues was to stay out of public view,” recalled retired Navy captain Roy Voris, the unit’s founder. “It was better to stay out of sight if we had a bad accident. We were a separate unit, not yet a command.”

Voris, who shot down eight enemy planes in WWII and was awarded three Distinguished Flying Crosses, said the Blue Angels were formed primarily to renew interest in carrier aviation in post-war America. “It was done to get the Navy visible again,” he added.

“They said there was only one candidate to lead the unit, and I was it. I selected the Hellcat because it was an honest machine and very stable. My concept of the show was to get it on, get it up and get it down in 15 minutes.”

Early Blues

Voris, who died in 2005 at the age of 85, had a hand in nearly everything about the fledgling Jacksonville-based squadron, from picking the pilots and ground crew to devising the dangerous flying sequences. Tall for an aviator, Voris had flown combat missions off two different carriers during WWII, serving as flight operations officer on one of the Navy’s most decorated carrier squadrons, “The Fighting 32nd.”

“Almost everybody was an ace,” he recounted. “It was either be an ace, or be killed. We stair-stepped through the Pacific flying day fighters equipped with .50-caliber machine guns. We saw a lot of action.”

After the war, he was assigned to teach fighter tactics at NAS Daytona Beach. In early 1946, he was reassigned to NAS Jacksonville as chief flight instructor and tapped to lead the Navy’s new “flight exhibition team.” Voris choose pilots he knew and trusted, including his former squadron mate on the USS Enterprise, Lt. Maurice “Wick” Wickendoll.

In 1946, a contest was held to name the unit. Among the suggestions: “Blue Bachelors” and “Blue Lancers.” Then Wickendoll showed Voris an advertisement for a nightclub in New York called the “Blue Angel,” the pair knew they had found their handle.

Fly Navy

Voris commanded the Blue Angels from 1946 to 1947 and through their transition into the faster Grumman Bearcat. He was tapped to lead the Blues again in 1951, after the unit was disbanded for a short time during the Korean War. As officer in charge, he demanded that all his pilots be bachelors. But during his second stint with the Blues, Voris broke his own cardinal rule – he got married when he was home on leave in Santa Cruz, Calif.

After retiring from the Navy in 1963, Voris became a consultant for Grumman Corp. and later worked in NASA’s Office of Industry Affairs. An air terminal at NAS Jacksonville is named in his honor. While today’s Blue Angels pilot supersonic jets, they still fly in tight formations, as close as a foot apart.

“My ability and confidence to fly in tight formations came from my war experiences,” said Voris, who started the Blue Angels when he was 27 years old. “Flying close quarters is the mark of the Blues.”

The 2019 Train Enclosure Project

If you’ve been by the Beaches Museum recently you will see a LOT of work going on with the building that houses the 1911 Cummer & Sons Locomotive! Known as the Train Enclosure, the building protects the locomotive and is always busy with visitors, field trips, birthday parties and more.

Do you want to be a part of the effort to repair the Train Enclosure? Donors of $20 or more to the project will have their name listed on a permanent sign that will be hung inside the Train Enclosure when the project is complete! List your name or that of someone who loves the train and they will be able to see it for years to come.

Join the City of Jacksonville, the Rotary Club of Ponte Vedra Beach, RG White Construction, Romano Bros. Roofing and McIntyre Stucco & Paint in making this project possible!

To donate visit the donation website or call Chris Hoffman at 904-241-5657 x 113.

This article was adapted by Archives & Collections Manager, Sarah Jackson, from the permanent exhibit “Waiting for the Train” and the 2017 exhibit “Atlantic Beach: From the Continental to a Coastal Community.”

Henry Flagler (1830-1913) lived “The American Dream.” He was born in Hopewell, New York and later moved to Bellevue, Ohio where he found work at the L. G. Harkness & Company store.

Henry Flagler

During his time in Ohio, Flagler organized several companies in the grain and salt industries before joining John D. Rockefeller, a fellow grain trader, and Samuel Andrews to found Standard Oil, a petroleum refinery. Soon, Standard Oil was doing one-tenth of all petroleum business in the United States and went on to become the largest and most profitable corporation in the world at its peak. Flagler’s involvement with Standard Oil steadily diminished after 1882, but he remained vice president until 1908.

In 1853, Flagler married Mary Harkness, the daughter of Lamon Harkness – owner of the general store where he was formerly employed. Mary’s health was poor throughout her life, although she and Henry had three children: Jenny Louise, Carrie, and Harry Harkness.

Flagler first came to Florida in 1878 when he and Mary came to spend the winter in Jacksonville, Florida in the hopes that Mary’s health would improve. Although she never regained her health and died in 1881, Flagler recognized potential for growth and tourism in Florida and went on to devote most of his remaining years to developing the area. Flagler was especially taken with St. Augustine after an 1883 trip to the area with his second wife, Ida Alice. He returned to St. Augustine within two years to commence construction on the Ponce de Leon and purchase the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, & Halifax Railroad. From these projects, Flagler established the Florida East Coast Railway.

Over the next several years, Flagler continued to purchase smaller, local railroads along the east coast of Florida and connect them to create a railway system unlike any Florida had yet seen, which would span from Jacksonville down into Key West. Other hotels were constructed along the line after the Ponce de Leon, creating a string of hotels that became the Florida East Coast Hotel Company. Around 1899, Flagler set his sights back toward the Jacksonville area and implemented this same pattern at the Beaches.

The Continental Hotel, ca. 1902.

The main objective with this new branch was to reach the docks at Mayport along the St. Johns River, which soon also became home to the company’s coal wharf. The coal was needed to fuel Flagler’s growing railway and hotels. The Jacksonville and Atlantic Railway ran from downtown Jacksonville toward Pablo Beach (now Jacksonville Beach). The Jacksonville, Mayport & Pablo Railway operated from the Mayport Village docks over to Burnside Beach on the oceanfront. Burnside Beach was a short-lived luxury resort complex that was built in conjunction with the JM&P Railway, but is now known as part of the land where Naval Station Mayport resides. These two railways were purchased by the FEC and connected along the oceanfront by 1900 to create the Mayport Branch of the FEC Railway. Another FEC Hotel was opened along this line in Atlantic Beach – the Continental Hotel.

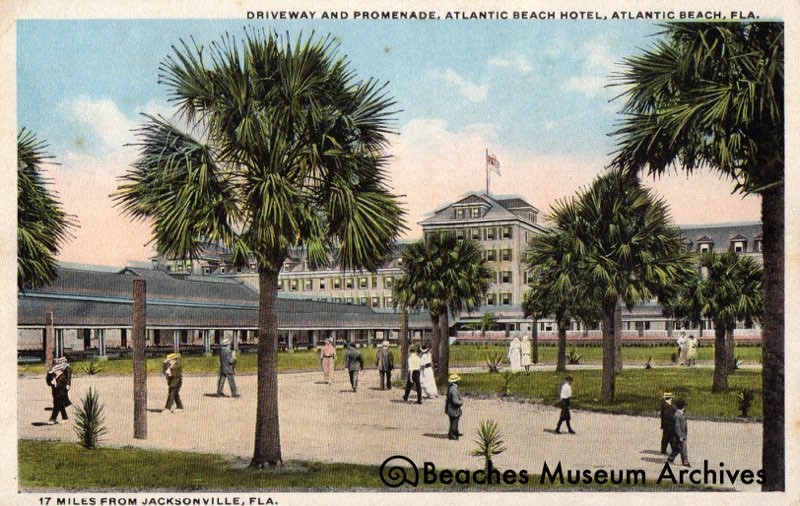

Postcard depicting the Continental Hotel (after it was renamed to the Atlantic Beach Hotel) as viewed from the railway.

The Continental opened in June of 1901. While it still featured luxury accommodations like Flagler’s other Florida resorts, it was simpler in design than hotels like the Ponce de Leon. The hotel featured its own golf course, a detached veranda that wrapped around the hotel for lounging, an 800 foot ocean pier – the Atlantic Beach Pier – for fishing, picturesque drives around the area, and automobiling and racing along the shore.

Stretching along the oceanfront at 447 feet long and 47 feet wide, the wooden hotel provided a grand and palatial figure at the Atlantic Beach seashore. The building was yellow – a specific shade used by the FEC – with green shutters, accommodations for over 200 people, and a dining room that could seat 350 people.

In advertisements for the hotel, the building was described as having an architectural design which was “perfectly balanced and pleasing to the eye” with its symmetry. It was also constructed close to the railway and boasted its own train station along the Mayport Branch.

The station for the Continental Hotel, also known as the Atlantic Beach Station.

Despite all of its advantages, the Continental – opened for both summer and winter seasons – was sold by the FEC in 1913 to the Atlantic Beach Corporation. It was then renamed to the Atlantic Beach Hotel until the building burned down in 1919.

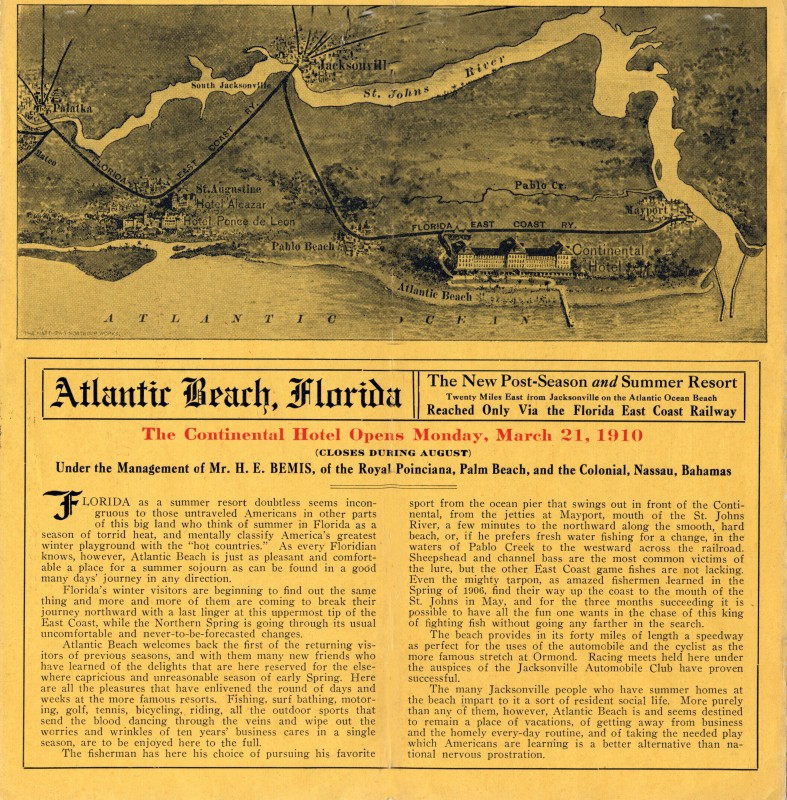

The inside of a brochure for the Continental Hotel after it was renamed to the Atlantic Beach Hotel, which depicts several scenes both inside and around the hotel.

The Mayport Branch continued to operate under the FEC well after the company had sold the hotel. Carrying passengers and cargo to and from the beaches, it remained a staple in local transportation for several years. However, by 1930, the FEC’s interest in the Mayport Branch had and local need for the railway decreased as other methods of transportation improved. Cars were already a regular sight at the beachfront, and in 1931, renovations and an electric drawbridge were completed for Atlantic Boulevard, allowing for greatly increased flow of traffic to the Beaches. The branch ceased operations in October 1932 and marked the end of an ear for the Beaches communities.

Part of a brochure for the Continental Hotel as it reopened for its 1910 season describing the amenities of the hotel and its surroundings.

Flagler never lived to see the end of the FEC in the Beaches area. In 1913, he fell at his home in Palm Beach and died on May 20. His legacy in Florida continues today both through the company and the communities that developed and expanded around the railway.