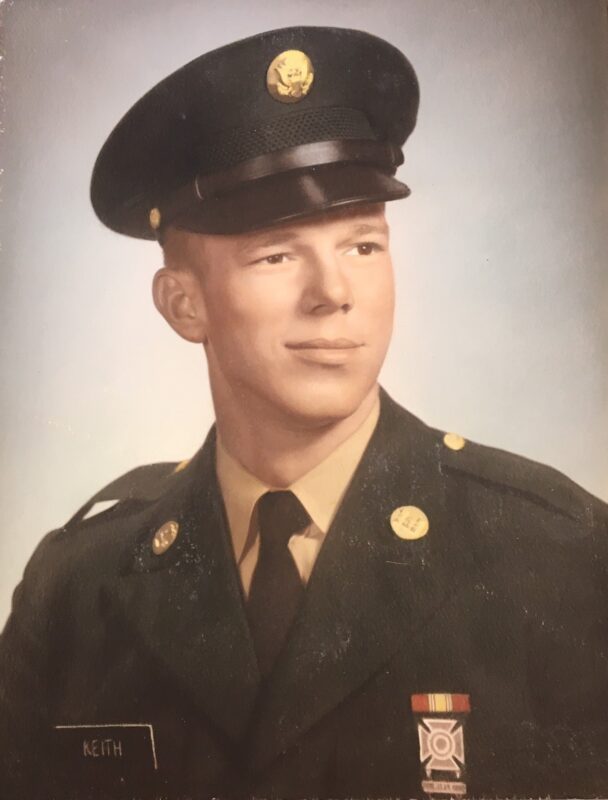

Rock soldier: Jimmie Keith did his duty and then some

Keith did his duty and then some.

By Johnny Woodhouse

After completing a 12-month tour of duty in Vietnam, Jimmie Keith had earned the right to return to the United States in the summer of 1969.

But like several men in his Army unit, the 19th Combat Engineer Battalion, Keith, a Jacksonville native who grew up at the Beaches, extended his overseas tour for another 90 days.

“Morale continues to be high in the battalion, as indicated by the high extension rate, attitude, appearance and accomplishments of the men of the 19th,” said Lt. Col. Gilbert Burns, the unit’s commanding officer, in a quarterly operational report dated April 1969.

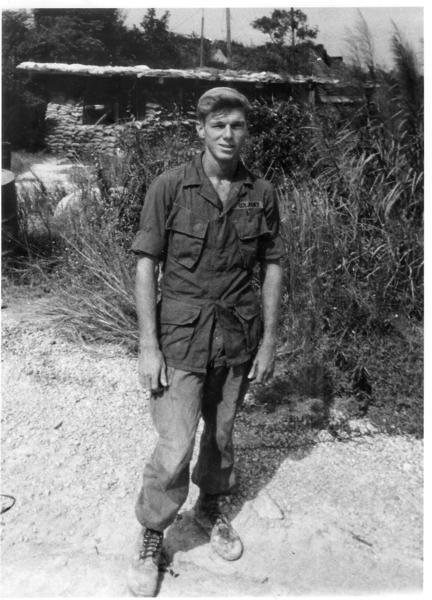

Army engineers like Keith played a vital role in the Vietnam War.

Besides helping to keep supply lines open, they were responsible for a wide range of tasks, including building and maintaining roads, bridges, and airfields.

In 1969, the primary mission of Keith’s unit was to upgrade and pave a 50-mile stretch of QL-1, a national highway and the major route between Saigon and Hanoi.

Nicknamed the “Street Without Joy,” QL-1 was “a very dangerous, contested, expensive and memorable stretch of road,” recalled Frederick J. Smith, a company commander with the 19th Engineers from December 1968 to October 1969 and now a historian with the 19th Combat Engineer Battalion Vietnam Association.

“This was a hostile area, and as engineers not attached to an infantry division, we had to provide our own defensive security, 24 hours a day. It was and still is a remote corner of Vietnam.”

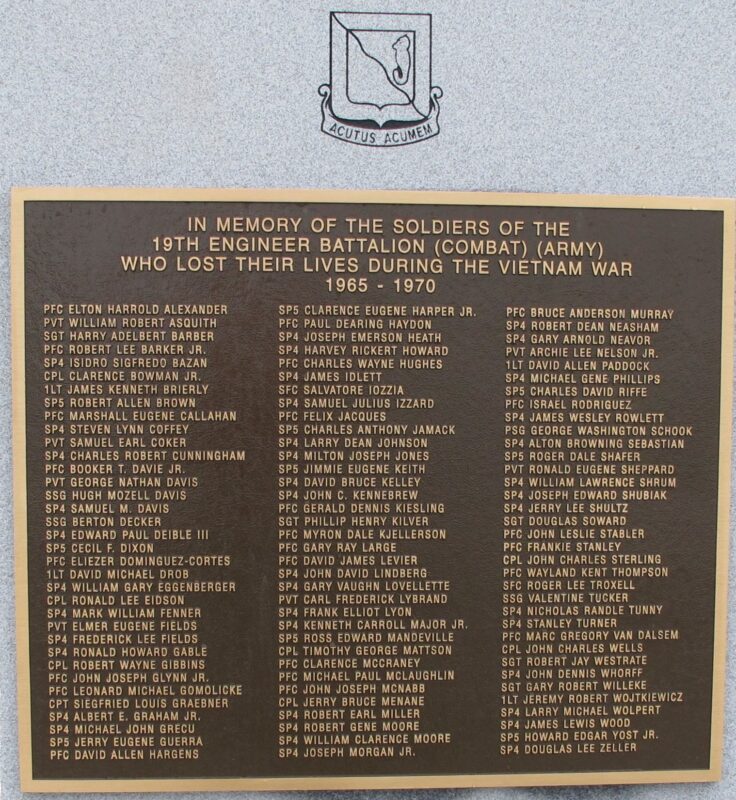

The 19th Engineers experienced their fair share of misery and heartbreak in Vietnam.

Between 1965-1970, 105 soldiers assigned to the unit died overseas and more than 400 others were wounded. Only one other combat engineer battalion in Vietnam suffered more casualties.

Wanted to finish the job

A quarry specialist, Keith was assigned to the 73rd Engineer Company, which was responsible for producing thousands of cubic yards of crushed rock and hot mix asphalt used for road paving projects.

The 73rd operated up to five rock crushers at the Tam Quan Quarry, including a pair of 225-ton crushers capable of producing more than 30,000 cubic yards of crushed granite rock of all sizes. Rock crushers were a vital link in the production of concrete.

“At Tam Quan, like any military quarry in the Republic of Vietnam, progress is measured in tons of rock and asphalt, and miles of roadway,” wrote Army Specialist Mike Barry in the summer of 1969.

“Its quarrymen blast rock, haul rock, crush it, heat it, spread it, and see it in their dreams at night. Their job is one of the dirtiest, most boring an engineer does, but it is one the of most important and they take it very seriously.”

The 73rd “operated one of the finest construction support facilities in Vietnam,” according to its commanding officer, and the unit, which was divided into five platoons, was nominated for the Itschner Award, an annual honor presented to the Army’s most outstanding engineering company.

With more than 60,000 pounds of explosive used in mining operations, quarry work was also inherently dangerous.

In March 1969, the 73rd added a night shift at the rock quarry when a nearby airfield resurfacing project was added to their list of combat support missions.

The 73rd resurfaced the airfield at LZ English in 22 days but kept the night crew going at the quarry to ensure that the battalion’s year-long highway paving project remained on schedule.

“He liked being in the military,” said Patricia Boatwright, one of Keith’s four sisters. “He wanted to finish the job.”

During his spare time, Keith managed the Enlisted Men’s Club at his dusty hilltop firebase situated about four miles from the South China Sea.

Loved working with his hands

In 1967, when Keith joined the Army, there were more than 35,000 combat engineers in Vietnam.

A year before he would join their ranks, Keith spent a year in Germany serving with another Army unit.

“He liked both the country and the people with the exception of the cold German winter,” wrote Helen “Patches” Musgrove in her 1986 book, “Vietnam: Front Row Center.”

“He says he’d like to visit there again just as a tourist.”

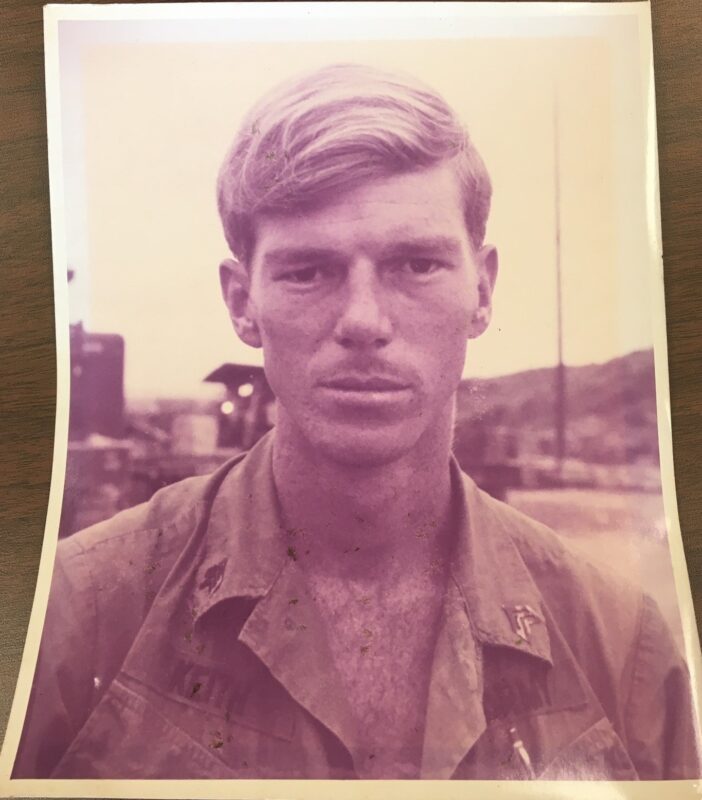

A war correspondent for The Jacksonville Journal, Musgrove interviewed Keith and another combat engineer from Jacksonville, Eddie Forrest, at their base, LZ Lowboy, in May 1969.

“Jimmie was a very pleasant young man who admitted that he had matured and altered his ideas about life considerably since joining the Army and coming to Vietnam,” said Musgrove, a former registered nurse who covered the war for more than six years.

“He had definitely made up his mind that he was going to complete his high school education when his Army duty was over, and he would like to return to his old job after he earned his diploma.”

When he turned 16, Keith dropped out of Fletcher Junior High to work fulltime for an Atlantic Beach business that made fishing tackle.

“He loved working with his hands,” recalled, Keith’s younger sister, Shirley Greenlaw, who attended Fletcher High in 1967.

“He used to ride to work on a motor scooter.”

Keith spent two years making fishing tackle at the Levy Road tackle shop before enlisting in the Army with Greenlaw’s late husband, Curtis.

Enlisting in the Army meant three years of active-duty service but entitled Keith to his choice of military occupational specialty. He and Greenlaw both chose the same branch of service – Army engineers.

Never asked for anything in return

During his chance meeting with the war correspondent in the spring of 1969, Keith reminisced about his mother’s home cooking and the North Florida beaches where he grew up.

He also confided in the correspondent that he had recently received a “Dear John” letter from a girl back home and was badly shaken by it.

“However, we discussed it and I believe I was able to help him accept what he could not change,” Musgrove said. “He was due home in another month but decided to extend in Vietnam.”

Soldiers who extended their tours of duty in Vietnam qualified for the Army’s Early Out Program, which basically relieved them of any further active-duty service once they returned to the U.S.

When Keith first received orders for Vietnam, he tried to keep it a secret from his family.

“He didn’t want his mom to worry,” said Shirley Greenlaw. “Jimmie was always her baby.

“But he ended up telling me where he was going and said, ‘I don’t want to go over there, because I won’t come back.’”

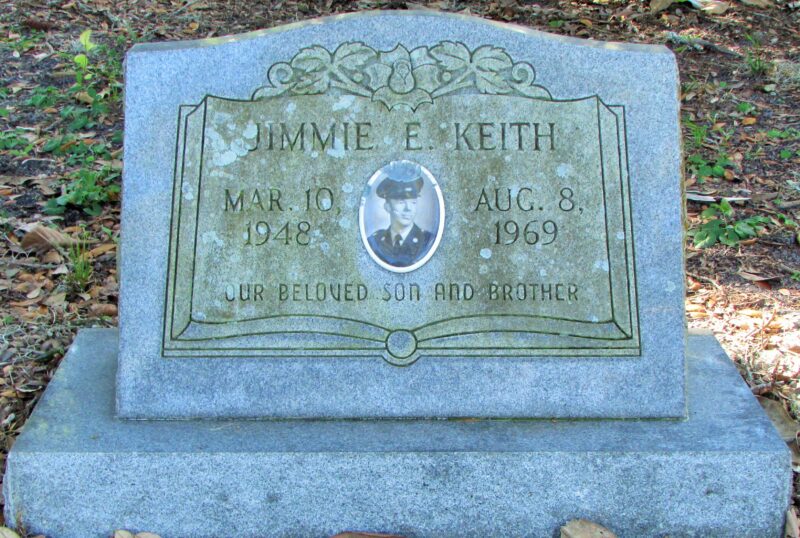

On Aug. 8, 1969, Keith’s worst fears, and those of his family members, came true.

The 21-year-old Army specialist was fatally injured at the quarry while working on a piece of heavy equipment known as a jaw crusher. He had less than a month to go in Vietnam.

Four days later, a memorial service for Keith, including a 21-gun salute, was held at LZ Lowboy, where he was stationed for more than 14 months.

“We must admit to ourselves that he is gone, but we will never forget him,” said members of the 73rd’s quarry platoon in a letter addressed to Keith’s family.

“He was one of those guys who was always happy, no matter how bad the scenario was. If someone on the team was down in the dumps, Jim would bring him out of it. That was the type of person he was – always giving and never asking anything in return.”

Pat Boatwright said she received a letter from her little brother about a month before his fatal accident.

“I didn’t open it for about a year and when I finally did it broke my heart,” she said.

Shirley Greenlaw said she was living on an Army base in Virginia when she received the sad news.

“If there was something wrong with a rock crusher, Jimmie would be the first one to try and fix it,” she said. “He was always a very careful person.”

Bronze star recipient

Keith’s remains were returned to Jacksonville Beach and interred at Warren Smith Cemetery.

Musgrove attended a memorial service for Keith at the Atlantic Beach Pentecostal Holiness Church and mentioned it in her Aug. 20, 1969, Jacksonville Journal column.

“I looked around me in the little church and noted that the military honor guard and pallbearers all wore Vietnam War campaign ribbons on their chest,” she said. “The type of men who came there to join in the last goodbye told me much about what sort of person Jimmie really was. … It was a silent testimony that Jimmie was a man’s man who made deep and lasting friendships.”

In February 1970, the Army presented Keith’s parents with a posthumous Bronze Star Medal for their son’s meritorious service in Vietnam. Keith’s other military decorations included the Good Conduct Medal, Vietnam Service Medal with one Bronze Service Star and the Military Merit Medal, which is the highest decoration bestowed to enlisted personnel by the Republic of Vietnam.

The 73rd Engineer Company received a Valorous Unit Award (VUA) for its heroic actions in Vietnam. The VUA is the second highest decoration an Army unit can receive after the Presidential Unit Citation.

“The men of the 19th Engineers were smart, well trained, hard working and brave,” said Smith, the former 19th company commander, and a 1965 West Point graduate.

“They always showed initiative and worked well as a team. I remain proud to have served with them and proud to say I was a combat engineer in Vietnam.”

A street sign has been erected in Keith’s honor in the 2100 block of 9th Avenue North in Jacksonville Beach. His name also appears on the Veterans Memorial Wall in Jacksonville and on Panel 20W, Line 113 of the Vietnam Veterans Wall in Washington, D.C.

Johnny Woodhouse has served as a guest curator, cemetery tour guide and frequent contributor to the Beaches Museum since 1999. A retired journalist who spent more than 30 years in the newspaper business, he is currently a freelance healthcare writer and budding Wikipedian.