Finding His Roots: Long-lost Kirkland Family Relative Journeys to Jacksonville Beach

by contributor Johnny Woodhouse

Manfred Muss has been searching for his biological father all his life.

An only child, Manfred knew his Austrian-born mother, Else, had a romantic encounter with an African American soldier in the early 1950s, but she died without ever telling him the soldier’s name or possible whereabouts.

Manfred, now 73, was resigned to the fact that he would never learn his father’s identity until one fortuitous day in 2006 when a picture frame fell off a wall at his home.

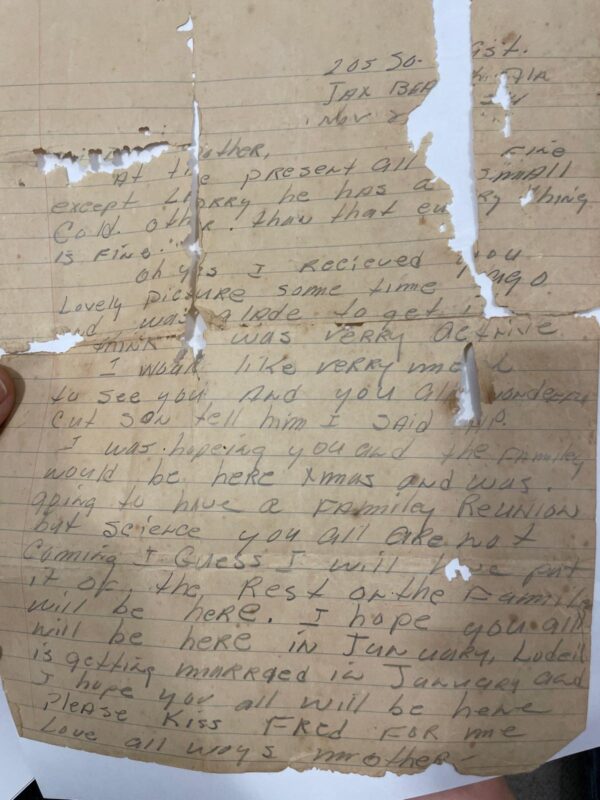

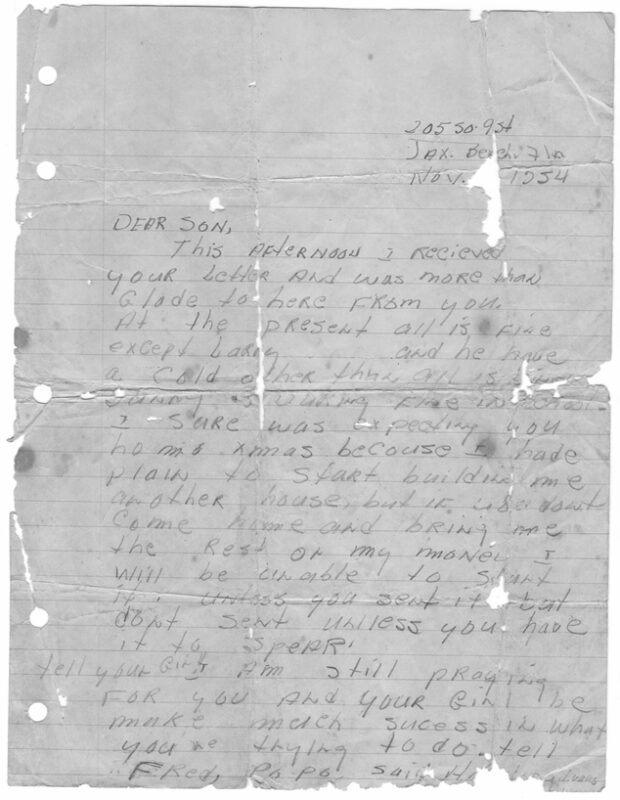

From behind the broken frame slide out two handwritten letters, both containing a mysterious Jacksonville Beach street address.

The letters, yellowed by time, were more than 50 years old and written entirely in English. Curious, he asked a friend to help him translate them.

After a few unsuccessful attempts, Manfred gave up and stowed the fragile letters away in an old leather suitcase.

Fast forward to October 2024. Manfred and his 35-year-old daughter, Thali, are having lunch at his home in Milan, Italy, when he casually hands her one of the letters.

Fluent in English, Thali immediately recognized something significant about it. The word “Fred” appears repeatedly. It was a nickname her father had been called as a child.

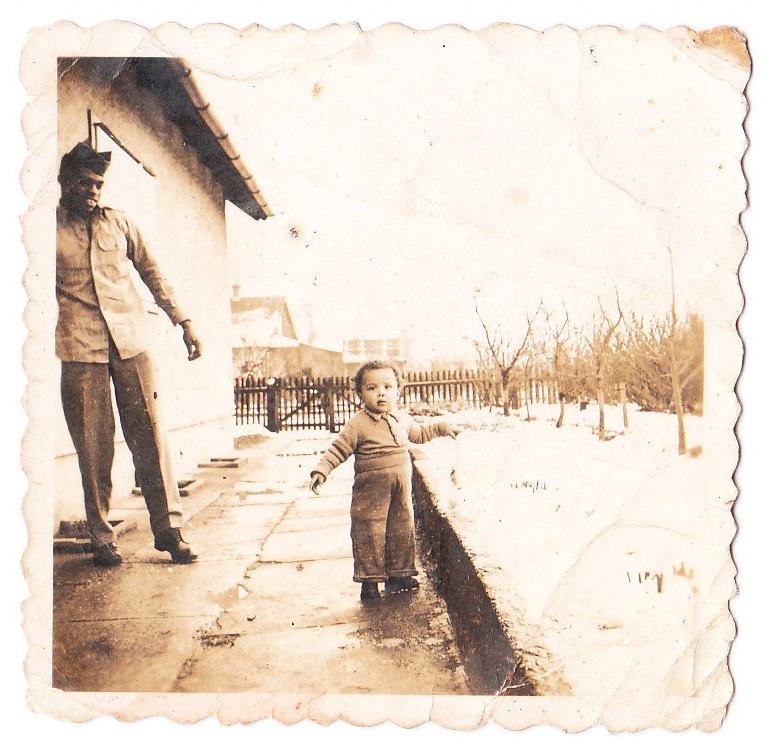

Prior to the discovery of the letters, the only evidence of her father’s ties to his African American roots was a treasured photograph from his childhood in post-war Linz, Austria.

In the sepia-toned photo, Manfred is depicted as a toddler standing with his arms outstretched as a uniformed African American soldier stands close by. Every time Manfred asked his mother about the photo, she would change the subject or make up stories that only deepened his confusion, Thali said.

“Her refusal had created a void, an absence my father had spent his entire life trying to fill,” she added.

Putting together the puzzle pieces

Driven by curiosity and the desire to solve the mystery that had weighed on her father for years, Thali decided to take matters into her own hands.

First off, she successfully reconstructed the return address at the top of the letters: 205 South 9th Street, Jacksonville Beach. Next, she posted her findings with a Jacksonville Beach Facebook group.

The responses included suggestions like contacting Search Angels, a nonprofit organization specializing in genealogy, or reaching out to the local property appraiser’s office.

“But the most valuable suggestion came from a Jacksonville Beach resident named Ashley Pardee, who advised us to contact the Beaches Museum, which houses the city’s historical archives and, according to her, has a wonderful team of volunteers,” Thali said.

Before contacting the museum, Thali matched the letter’s return address to census records on Ancestry.com. After some trial and error, she hit the jackpot. The 1950 census listed an African American family with the surname Kirkland residing at 205 South 9th Street, Jacksonville Beach.

Four of the occupants of the home were mentioned prominently in her father’s letters.

“Every name was a confirmation. The past I had been chasing was no longer an undefined haze. It was taking shape before my eyes,” Thali said.

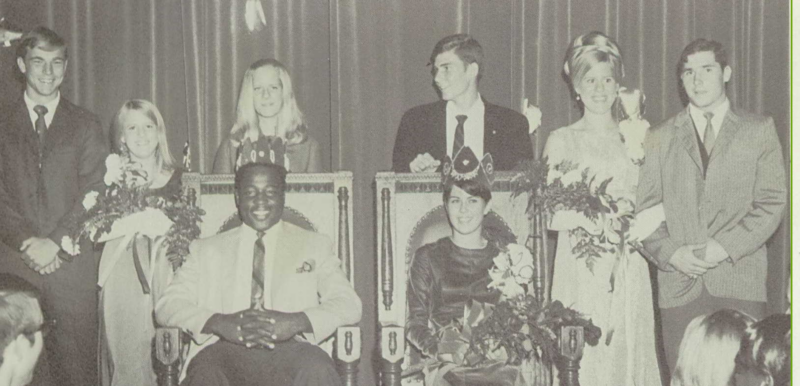

One name on the census record stood out to her – Junior Kirkland. Could he, in fact, be her father’s biological father? Everything seemed to point in that direction.

Connecting with his overseas kin

After taking Ashley’s advice, Thali sent an email, on behalf of her father, to the Beaches Museum, inquiring about the existence of Junior Kirkland.

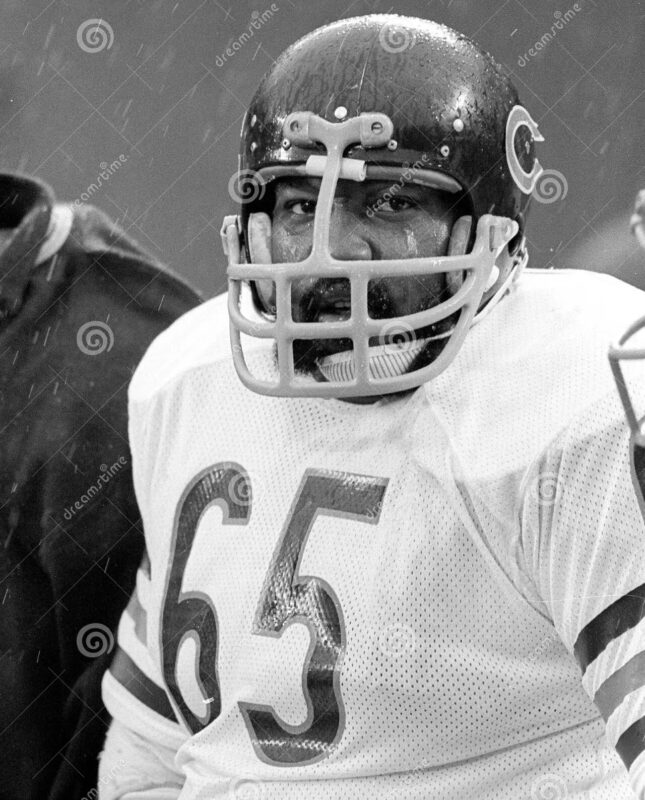

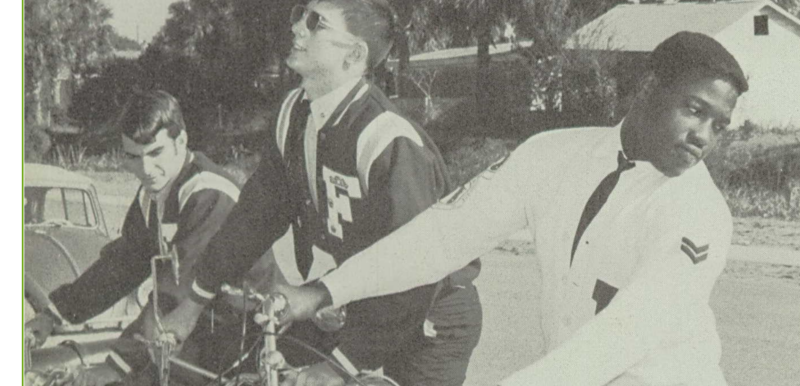

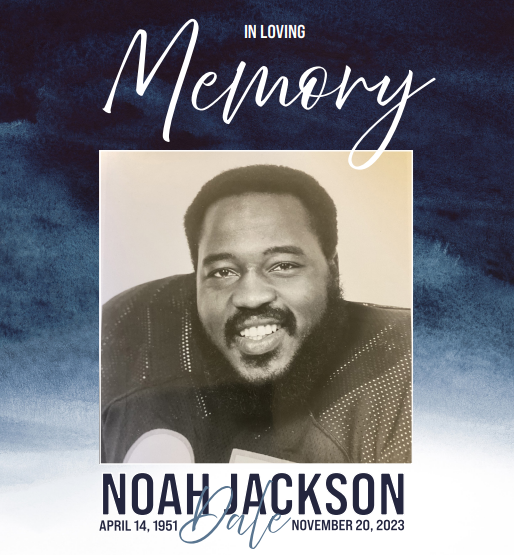

After some poking around on the Internet, I was able to find Gus Kirkland Jr.’s obituary and burial details. A 1950 graduate of Stanton High School, he spent more than 20 years in the U.S. Army, rising to the rank of sergeant first class. After his military career, he opened several businesses in Washington D.C., including a soul food restaurant that was frequented by President Obama.

Sadly, Gus. Jr. passed away on April 26, 2013. He was 81.

Knowing her father would never be able to meet his father face to face was a hard pill to swallow. But Thali did the next best thing: she purchased two roundtrip plane tickets from Milan to Jacksonville so her father could meet several members of the Kirkland family still residing in Jacksonville, including an aunt and several first cousins.

On Saturday, March 8, the museum hosted a special Kirkland Family Reunion for Manfred and Thali which drew more than two dozen of his closest relatives.

The private event was held in the Museum lobby and the Italian guests of honor were able to connect with other descendants of Lee Kirkland, the former Alabama sharecropper who moved his family to Jacksonville Beach in the early 1940s.

Lee Kirkland was the unofficial caretaker of the former African American cemetery in Jacksonville Beach. After his death in 1960, the city of Jacksonville Beach named the cemetery in his honor.

On Sunday, March 9, Manfred and Thali visited the cemetery where several Kirkland family members are buried, including Manfred’s grandparents Gus Sr. and Effie Kirkland, who proudly displayed photos of Manfred and his mother in their Jacksonville Beach home.

Father and daughter also made pilgrimages to the historic St. Andrew A.M.E. Church where Gus Sr. was a trustee, the Rhoda L. Martin Center on South 4th Street, where Gus Jr. attended grade school and old Stanton High School in downtown Jacksonville.

Before flying home to Milan on March 17, Manfred and Thali made a stopover in Knoxville, Tennessee, to visit John Kirkland, the younger brother of Gus Jr., and a retired U.S. Air Force veteran.

“In hindsight, I understand how important it was for my father to confront this challenge,” said Thali. “Roots are not just a connection to what was but a guide to understanding where we are and where we can go. I am grateful to have found the strength to embark on this journey, too.

“Discovering one’s origins is not just about answering lingering questions, but embracing the choices, losses, and realities of those who came before us,” she added.” My father experienced this journey with hesitation, torn between the desire to know and the fear of not ever knowing. In the end, he experienced a liberation, knowing that every fragment of the past is a part of who we are today.”