Beaches Tidings Spring 2019

The Spring 2019 Newsletter is now available to read online!

The Spring 2019 Newsletter is now available to read online!

This article was written by Beaches Museum Archives & Collections Manager, Sarah Jackson.

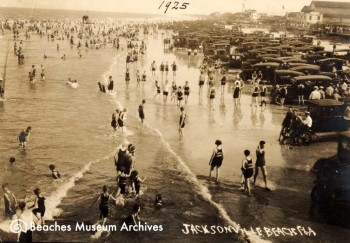

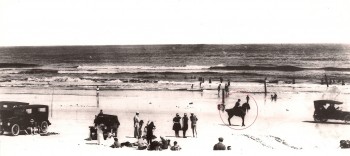

Though Pablo Beach only became an incorporated city in 1907, the community was already well on its way to becoming a popular beach destination on the Floridian coast of the Atlantic Ocean. Before 1912, however, residents and visitors to Pablo Beach, now known as Jacksonville Beach, swam in the ocean waters at their own risk. Over the years accidents occurred with inexperienced bathers, and even experienced bathers, caught in rip currents and other dangerous situations in or near the water. There were no trained officials at the beach to help bathers in distress and the closest medical facilities were miles away in Jacksonville.

This photo shows the Jacksonville Beach beachfront filled with crowds of bathers and cars in 1925.

The United States Volunteer Life Saving Corps of Pablo Beach was founded in 1912 by Clarence H. McDonald and Dr. Lyman G. Haskell. McDonald was appointed supervisor of public recreation for Jacksonville by the city government that year. Shortly after he took up his new position, a young nurse drowned in Pablo Beach, which brought the lack of beach lifeguards and first aid to McDonald’s attention and set him on the path creating the Corps. As he began efforts to start a life saving organization, he met Dr. Haskell, the Physical Director of the Y. M. C. A. in Jacksonville at the time who had also recognized the great need for such a group and joined McDonald’s efforts. Haskell created swimming and gymnastics classes in 1912 which became the basis for future Corps training, and many of his students from these classes became the first members of the U. S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps.

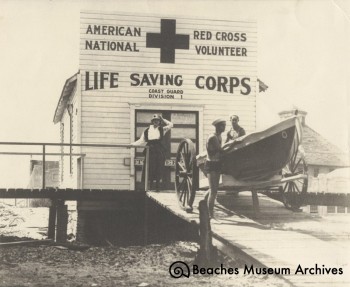

The first building for Station #1, ca. 1913.

The Corps officially opened its first station, funded by the city, on April 6, 1913. This first station was a wooden structure just large enough to house one or two boats, some equipment, and a handful of men. The small building quickly became insufficient to fulfill the needs of the volunteer lifeguards, but continued to serve as their station for several years.

Less than two years after its inception, the Corps experienced a significant change. Due to the efforts of Commodore Wilbert E. Longfellow, the American Red Cross began its water safety program in 1914, and the U. S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps was chartered on April 17 of that year to become the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps, Coast Guard Division #1. The small Pablo Beach station became known as Station #1.

The first building for Station #1 as it looked after 1914. The name of the front of the station was changed to reflect the group’s new identity as the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps, Coast Guard Division #1.

The first building, however, was prone to storm damage, even blowing over a couple of times during significant storms in its earliest years before being fixed to a concrete foundation around 1915. While the Corps made frequent repairs over the years, it was ultimately replaced in 1920. Made of concrete block, the second Station #1 housed first-aid rooms, a guard room, locker room, captain’s room, club room, and a dormitory. A few years later, a boat room and a second dormitory were added. This station weathered several hurricanes and served the Corps for almost 25 years.

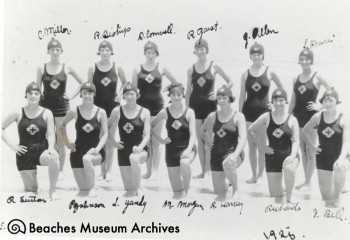

In its early years, the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps had a contingent of women guards. Formed in the late 1920s, they served the beach community for about a decade. Since the mid-1990s, women have been actively recruited to serve alongside their male colleagues as one unified corps.

In its early years, the American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps had a contingent of women guards. Formed in the late 1920s, they served the beach community for about a decade. Since the mid-1990s, women have been actively recruited to serve alongside their male colleagues as one unified corps.

Talks began as early as the late 1930s to either remodel the station or replace the structure entirely. The second station was eventually torn down in December of 1945 and construction began on today’s Station #1 in 1946. Initially, the new station was expected to be built and operational in 1946, but due to problems with financing and materials needed for construction which were in short supply as WWII had only recently ended, construction was delayed for several months. Lifeguards and new recruits operated out of an old army hut on the beachfront throughout construction.

Full operations in the third Station #1 building began in 1948 with several improvements including a new observation tower known as the Peg. The older version of the Peg, similar to the mast and crow’s nest of an old ship, was replaced by a five-story tower connected to the main building. Constructed with the Art Deco style of architecture, the layout of this station is similar in many ways to the one it replaced.

The second building for Station #1, ca. 1940.

The American Red Cross Volunteer Life Saving Corps remains an iconic and crucial component of Jacksonville Beach and the surrounding area. Station #1 was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014 and remains a focal point of Jacksonville Beach to the present day. The distinctive suits and red chairs that pepper the beaches throughout the summer months have remained unchanged for years. The organization continues to provide valuable services to the community including first aid and water safety education.

**The Volunteer Life Saving Corp, Inc. (VLSC) was established as a separate corporation in 2015.

Local lifeguards participating in the annual Meninak Ocean Marathon Swim around 1948 at the newly constructed third incarnation of Station #1. Photo by Virgil Deane.

Jacksonville Beach lifeguards on duty just north of the old pier, ca. 1926.

Lifeguards demonstrating drills to spectators in front of Station #1 in Jacksonville Beach in the 1920s.

This article was written by Spring 2019 Beaches Museum intern, Savannah Brychta

Without Jean H. McCormick’s decades of hard work and determination, much of the history of the Beaches’ area was in danger of being lost forever. Destined to fill a void many did not yet realize, Jean began her life as a proud and deeply involved member of the Beaches community.

The Hadens in front of the Oceanic Hotel (ca. 1929)

Jean Haden was born on May 1, 1921, in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father, a credit manager by trade, was advised by his doctor to seek out the coastal Florida air as treatment for his perennial health issues. At only six-years-old, Jean moved with her family to Jacksonville Beach, Florida. After settling in, her father purchased an old Catholic orphanage on the beachfront and converted it into the Oceanic Hotel.

Growing up within the walls of the Oceanic, Jean had the formative experience of watching her parents work hard to build and maintain a community institution. Her father managed hotel operations until his death, when Jean was sixteen. After that, her mother took over, eventually passing the hotel over to Jean herself. It was there that she interacted with the many characters that passed through the Oceanic’s doors, and it was there that she met J.T. McCormick.

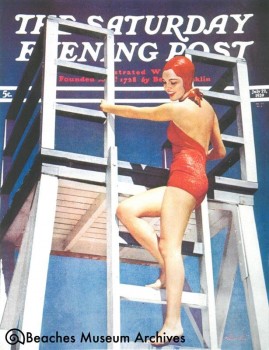

Jean McCormick on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post

In her early teens, the hotel was threatened by a violent tropical storm. Jean’s father called upon B.B. McCormick & Sons to construct an emergency bulkhead to shield his establishment from the expected storm surge. J.T. was one of those sons. The hotel survived and a romance was born. A few years later, J.T. and Jean began dating. Just before his death, Jean’s father told her that as long as she finished high school first, he would happily give his blessing for the two to marry. In 1939, Jean graduated from Duncan U. Fletcher high school and became Mrs. J.T. McCormick. The couple moved to the undeveloped Penman Road and started their family.

While J.T. followed in his father’s footsteps, expanding the community’s infrastructure, Jean became a significant member of the Beaches’ social structure. Her involvement in the community’s affairs grew to the point that she was able to identify societal needs and worked to fill them. Her passion and tenacity resulted in the establishment of a Dental Clinic for underprivileged children, the foundation of the Azalea Garden Circle, and the creation of a study group for local women to meet and discuss current events and other intellectual topics.

Phyllis Webb (left) and Jean McCormick (right) on the beach, photo by Virgil Deane (1948)

Jean also served as a president of the Junior Women’s Club of Jacksonville Beach. She served six years on the Jacksonville Episcopal High School Council and was vice president for two. She was president of the Women of Christ Church in Ponte Vedra Beach and president of the Friends of the Library at Jacksonville University. She served two three-year terms on the Jacksonville Historic Landmarks commission. She may not have realized it at the time, but working as a community leader in these organizations, Jean was building the skills and connections she later used to found a historical society. But it was that study group that planted the seed.

In 1976, in light of the nation’s bicentennial, Jean and the rest of the country began reflecting more on their collective pasts. Jean used it as an opportunity to research and talk about the history of the Beaches area with her study group. The local library offered only a single book on Beaches history. She was instructed to go downtown to find more.

Frustrated and motivated, Jean began to wonder why the Beaches were not the keepers of their own history. The Intracoastal Waterway (affectionately known as “the Ditch”) has long been a border between the Beaches area and Greater Jacksonville. As a result of this geographical divide, the communities on either side have evolved with some degree of separation, one that has birthed a distinct local identity at the Beaches. Jean began to wonder how one might go about preserving the story of that identity’s evolution.

By 1978, she was in contact with her old friend J.B. Dobkins who worked for the Florida Historical Society in Tampa. Under his advice, and with the support of her close friend Virgil Deane, Jean began taking the temperature of local interest in the idea of forming a Beaches Historical Society. The response was overwhelming. McCormick later recalled that the project’s momentum took on almost divine proportions. “The Lord meant this to be,” Jean told the Sun-Times in 1981 when talking about how “doors had been opened” to her in the early stages of her efforts. By 1979, the Beaches Area Historical Society had embarked on their mission to “Plan a Future for Our Past.” In 1981, they opened the Beaches Museum.

Author James A. Michener, Jean Haden McCormick, J.T. McCormick (1981)

It takes a certain kind of person to pull together such a great achievement through sheer force of will. But looking over her life, it is easy to see how well-suited Jean McCormick was to the task. Jean loved Beaches history because she had lived Beaches history. She managed the Oceanic Hotel where she later discovered German spies likely stayed there, disguised as vacationing artists who were only walking the coastline in search of information. The FBI later visited, investigating their suspicion that those long ocean-side walks were taken with the purpose of mapping the coast for a landing and attempted infiltration by Nazi saboteurs in Ponte Vedra during World War II. Jean later oversaw the preservation of the wild invasion story with a historical marker in Ponte Vedra Beach.

Jean was also part of the foundation of many local institutions. Jean was in the second graduating class at Fletcher High School. She was the first bride to walk down the aisle at Beach United Methodist Church. These experiences instilled in her the sense of community that inspired the formation of the Historical Society. She has described her passion as “sentimental,” but it is precisely that ability to find meaning in things of the past that has saved Beaches history from being lost to the currents of time.

J. T. & Mrs. McCormick Attending “Saturday in the Park” during Centennial Celebration, museum in background (1984)

It would seem that she always had her keen sense for preservation and resourcefulness. When Jean and her husband moved from Jacksonville Beach to build a home in Ponte Vedra Beach, she salvaged timbers from her family’s Oceanic Hotel to use for construction. When the Beaches Museum opened in 1981, everything was donated. When the locomotive was acquired, the transport and construction was all fundraised.

She had long possessed the qualities of a leader. As a hobby, Mrs. McCormick was fond of constructing miniatures of homes and buildings. She would build them to scale and curate them with a meticulous attention to detail and loyalty to authenticity. Those same attributes were apparent in her leadership over the foundation and administration of the Beaches Area Historical Society.

In 2006, when the expanded Beaches Museum was completed, Jacksonville Beach Mayor Fland O. Sharp recognized Jean McCormick’s contributions by proclaiming March 7, 2006 to be Jean Haden McCormick Day. Following her recent passing and with that date only weeks away, we ask you to join us in remembering the life and accomplishments of Jean McCormick for Women’s History Month. The Mother of Beaches History—without her, our past would have been washed away by the waves.

In lieu of flowers, the McCormick family has requested that gifts may be made to the Jean McCormick Founders’ Fund at the Beaches Museum. This fund will help to ensure the lasting legacy of Jean McCormick. To donate online, please click here. Thank you.

The Beaches Museum offers educational field trips for children all year round! The combination of our Permanent Exhibit, rotating temporary exhibits, 5 historic buildings, a 1911 steam locomotive, and our Heritage Demonstration Garden, creates a unique learning experience for people of all ages.

If the number of students is above 50 per group, the Museum will contact you to arrange multiple field trip sessions. It is required to have 1 adult chaperone per 10 students. This is to ensure quality field trip time for all students.

Do your children love trains? Let them experience the time when the railroad ran through town. They will get to ring the bell on a real steam locomotive and learn about what life during the turn of the century as they tour Pablo Historical Park. Your little engineers will want to make tracks to visit again and again! Our youngest visitors will enjoy this fun learning experience as they participate in an interactive storytelling activity and search for objects on their VPK Scavenger Hunt while a docent tells them all about each item as they find it.

Program fee: $4.00 per student, chaperones and teachers free

Length of Program: 1 to 1.5 hours

This program was designed to support Florida State Standards. Educators are free to access Beaches Lower Elementary Curriculum Guide that contains pre- and post-visit activities and lessons for the classroom.

Program fee: $4.00 per student, chaperones and teachers free

Length of Program: 1 to 1.5 hours

Visit the Beaches Museum and explore the history of pioneers at the Beaches, discover who Henry Flagler was, and experience the innovation of the railroads! Students are guided on a tour of the Museum and History Park with an experienced docent. The field trip begins with a scavenger hunt in our Permanent Exhibit featuring the six beach communities of Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, Jacksonville Beach, Ponte Vedra, and Palm Valley. Students will then move through the 1911 Steam Locomotive, the 1900 Florida East Coast Mayport Depot, and the 1900 Florida East Coast Foreman’s House completing different activities and having the stories of each building brought to life by the docent. Finally, students will discover our Heritage Demonstration Garden, maintained by the Master gardeners through the University of Florida IFAS program. In the garden they will have the opportunity to learn about seasonal vegetables, sugar cane, and composting. Students will gain a richer understanding of local history and gain a valuable experience in this fantastic beaches culture.

This program has been designed to support 4th grade Florida State Standards. Educators can access the Beaches Museum Upper Elementary Curriculum Guide which contains pre- and post-visit activities and lessons for the classroom.

Program fee: $4.00 per child, chaperones and teachers free

Length of Program: 2 hours

The Beaches Museum welcomes all home school groups looking for educational field trip opportunities! Students will learn local Florida history when they visit the Museum and have the opportunity to experience that history through our historic buildings. Home school groups may customize their field trips to best match the age range and grade levels of your students. Options include: completing a scavenger hunt in the Permanent Exhibit, covering the beach communities of Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, Jacksonville Beach, Ponte Vedra, and Palm Valley, touring our 1903 Post Office, 1911 Steam Locomotive, 1900 Florida East Coast Mayport Depot, 1900 Florida East Coast Foreman’s House, and 1887 Beach Chapel, and interacting with the Master Gardeners in the Heritage Demonstration Garden.

Program Fee: $4.00 per student, chaperones and teachers free

Length of Program: 2 hours

The Beaches Museum welcomes all summer camp groups looking for field trip opportunities! Field trips are customized to best fit the age range, grade levels, and focus of each summer camp program. Options include learning about the railroads in Florida, particularly the Florida East Coast Railway and Henry Flagler, discovering Florida Friendly and sustainable gardening in the Heritage Demonstration Garden, beach history of Mayport, Atlantic Beach, Neptune Beach, Jacksonville Beach, Ponte Vedra, and Palm Valley, and much more!

Program Fee: $4.00 per student, chaperones and teachers free

Length of Program: 2 hours

|

|

This article was written and contributed by Karen Thomas

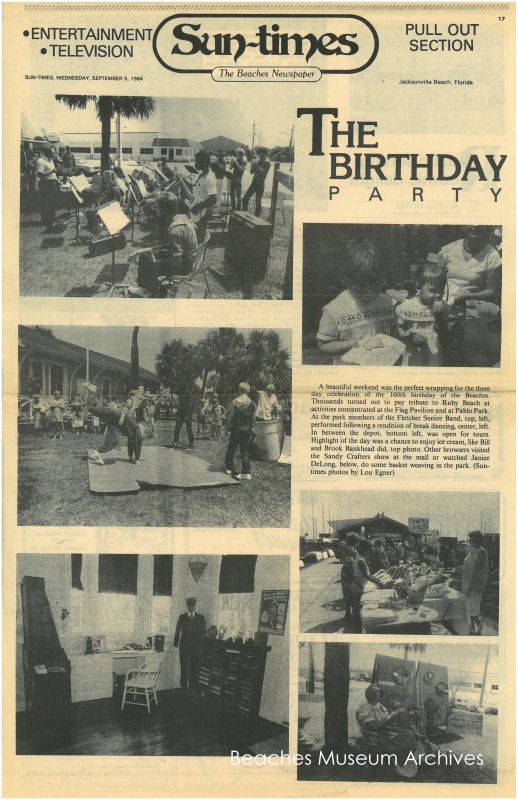

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.

In 1984, the Beaches Area Historical Society hosted a series of events recognizing the centennial of Jacksonville Beach. Founded in 1884 by the Scull family, Jacksonville Beach was first known as Ruby Beach. William E. and Eleanor Scull were the first family to settle the area, working a post office and general store while living in tents on the beach with their two children, Ruby and Bessie. What began as a small, nearly unpopulated, nineteenth-century outpost on the route between Mayport and St. Augustine eventually grew into the thriving and lively Jacksonville Beach that Jean McCormick and the Beaches Area Historical Society wanted to commemorate with a centennial celebration in 1984.

The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.

The celebration kicked off in 1983 when Florida Governor Bob Graham signed a proclamation designating 1984 as “Jacksonville Beaches Area Centennial Year.” From there, the Historical Society – led by Jean McCormick – spearheaded plans to ensure that the centennial celebration of Jacksonville Beach would be a year full of activity and events.

In April of 1984, the Society hosted a “Saturday in the Park” event to commemorate several significant milestones in Beaches area history.

First, there was the unveiling and dedication of the 1932 Lindbergh Baby Monument at its new permanent home in Pablo Park. This was followed by a ribbon cutting ceremony of the newly renovated and restored Mayport Depot. “Saturday in the Park” proved to be a huge hit, even drawing attendance from the grandchildren of the Scull family.

Jacksonville Beach’s centennial celebrations concluded in December of 1984 when the Beaches Area Historical Society placed a historic marker in Pablo Historical Park to commemorate the establishment of Ruby Beach. The grandchildren of William E. and Eleanor Scull initiated this idea and worked closely with the Historical Society in order to preserve this important piece of Beaches history.

The Beaches Mu seum needs your memories! Where did you go to hear the latest music with your friends on a Friday night back in the day? Music has long been an important part of life and a way to fall in love with the Beaches area. The Museum hopes to preserve local music history and culture through your stories. You can tell your stories by recording oral history interviews, lending concert programs, posters, t-shirt. Whether you attended the first Jazz Festival in Mayport or were a part of the weekend scene at pier dances or Einstein-A-Go-Go concerts, your memories and experiences are priceless. The Museum will showcase your memories at our upcoming exhibit opening in March 2019. Please contact Sarah Jackson , the Archives & Collections Manager at sarah@beachesmuseum.org to schedule donations.

seum needs your memories! Where did you go to hear the latest music with your friends on a Friday night back in the day? Music has long been an important part of life and a way to fall in love with the Beaches area. The Museum hopes to preserve local music history and culture through your stories. You can tell your stories by recording oral history interviews, lending concert programs, posters, t-shirt. Whether you attended the first Jazz Festival in Mayport or were a part of the weekend scene at pier dances or Einstein-A-Go-Go concerts, your memories and experiences are priceless. The Museum will showcase your memories at our upcoming exhibit opening in March 2019. Please contact Sarah Jackson , the Archives & Collections Manager at sarah@beachesmuseum.org to schedule donations.

The Holidays 2018 newsletter is now available!

Holiday 2018 cover

This article was written and contributed by Johnny Woodhouse.

Wonderwood by the Sea, her 375-acre estat in East Mayport, eventually grew to more than 20 buildings, including the Ribault Inn, a lodge and dining facility. Her two-story, white stucco manor that overlooked Ribault Bay was known as “Miramar,” which means sea view in Spanish.

Wonderwood By the Sea featured a 1,000-foot fishing pier, riding stables, a swimming pool, ball fields and an artificial lake. It was once the setting for a 1916 silent film. That same year, Stark was credited with organizing the first Girl Scout Troop in the Jacksonville area, Cherokee Rose Troop 1, made up mostly of girls from Mayport. During World War I, the Girl Scout troop played an active role in civil defense by patrolling local beaches on horseback.

In the ensuing years, Stark hosted numerous dignitaries at Wonderwood by the Sea, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, U.S. Senator Duncan Fletcher, Baron and Baroness DeWitt of Denmark, Colonel William Gaspard of France, and Jacksonville Mayor John Alsop.

Many of these prominent guests came to Wonderwood By the Sea as a result of her brother, Herman Hoffman Philip, an American diplomat and a former Rough Rider with Teddy Roosevelt.

But in 1940, life at Wonderwood by the Sea – and for Mayport as a whole – changed forever when the U.S. government waged an eminent domain battle for Stark’s land.

In 1926, Stark’s properties were worth an estimated $2 million. In 1940, the U.S. government offered her less than $40,000.

When Stark refused to leave, U.S. Marines forcibly occupied the Ribault Inn and later carried her out of her home tied to a chair. With her government settlement, Stark purchased 30 acres of undeveloped property south of the base, off what is now Pioneer Drive. She dubbed her new home Wonderwood Estates.

Stark spent her remaining years there until her death in 1967 at age 91. Once the belle of many official balls, she died alone and penniless and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Pablo Cemetery. Her husband, Jacob, a former prizefighter, preceded her in 1956.

In 1975, the Beaches Neighborhood of Girl Scouts, spearheaded by Brownie Troop 446, raised funds to mark her final resting place with a pink granite headstone etched with the Girl Scouts emblem. In 2010, the Mayport Civic Association recognized Stark’s memorable contributions to the historic fishing village with an additional marker at the foot of her modest grave.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.

apping up its 40th year by rolling out a new name and logo. Started in 1978 as the Beaches Area Historical Society, the organization has been a staple in the community with the mission “to preserve and share the distinct history and culture of the Beaches area”.